Notice

Disclaimer

Engineers Canada’s national guidelines and Engineers Canada papers were developed by engineers in collaboration with the provincial and territorial engineering regulators. They are intended to promote consistent practices across the country. They are not regulations or rules; they seek to define or explain discrete topics related to the practice and regulation of engineering in Canada.

The national guidelines and Engineers Canada papers do not establish a legal standard of care or conduct, and they do not include or constitute legal or professional advice

In Canada, engineering is regulated under provincial and territorial law by the engineering regulators. The recommendations contained in the national guidelines and Engineers Canada papers may be adopted by the engineering regulators in whole, in part, or not at all. The ultimate authority regarding the propriety of any specific practice or course of conduct lies with the engineering regulator in the province or territory where the engineer works, or intends to work.

About this Engineers Canada paper

This national Engineers Canada paper was prepared by the Canadian Engineering Qualifications Board (CEQB) and provides guidance to regulators in consultation with them. Readers are encouraged to consult their regulators’ related engineering acts, regulations, and bylaws in conjunction with this Engineers Canada paper.

About Engineers Canada

Engineers Canada is the national organization of the provincial and territorial associations that regulate the practice of engineering in Canada and license the country's 295,000 members of the engineering profession.

About the Canadian Engineering Qualifications Board

CEQB is a committee of the Engineers Canada Board and is a volunteer-based organization that provides national leadership and recommendations to regulators on the practice of engineering in Canada. CEQB develops guidelines and Engineers Canada papers for regulators and the public that enable the assessment of engineering qualifications, facilitate the mobility of engineers, and foster excellence in engineering practice and regulation.

About Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

By its nature, engineering is a collaborative profession. Engineers collaborate with individuals from diverse backgrounds to fulfil their duties, tasks, and professional responsibilities. Although we collectively hold the responsibility of culture change, engineers are not expected to tackle these issues independently. Engineers can, and are encouraged to, seek out the expertise of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) professionals, as well as individuals who have expertise in culture change and justice.

1 Background

1.1 Motivations and Relationships

Published on: June 2023

Engineers play a role in serving society through application of engineering principles to improve our communities while holding paramount the protection of the public.[1] In order to serve communities appropriately, Engineers must have an understanding of their values, goals, priorities, and context. Within this context, there are many cases where inadequate or non-existent consultation and engagement practices with Indigenous communities have caused or perpetuated harms.

The motivations for developing this guideline are drawn from this recognition as well as from pivotal works of reflection, truth telling, and appeals for action, such as the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People (RCAP),[2] the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Calls to Action,[3] the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) Calls for Justice,[4] and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)[5]. The act of reconciliation is defined by the TRC[6] as:

Establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal [i] and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country. In order for that to happen, there has to be awareness of the past, an acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour.

This guideline reflects Engineers Canada’s desire to strengthen relationships and to contribute to improved community outcomes and collective healing. Relationship building goes beyond engineering projects. The content of the guideline, and the conversations it initiates, are intended to empower the user to practice engagement with humility and empathy.

1.2 Consultation and engagement

The terms consultation and engagement carry different meanings, despite often being used interchangeably. The Crown has legal duty to consult[ii] Indigenous communities and possibly accommodate when a decision will impact asserted or established Aboriginal rights.[7] Engagement differs from consultation in that it involves building relationships outside of legal obligations with the intention of establishing trust and understanding and seeks reciprocity between parties, regardless of whether the engineer or firm is acting on behalf of the Indigenous community or for a proponent not affiliated with the community.

The act of consultation is more than an exchange of information and note taking. It should represent a willingness to listen and discuss Indigenous Peoples’ concerns and to be prepared to accommodate their concerns.[8] Engagement explores opportunities beyond community involvement in the project delivery, such as the supporting their efforts to assert sovereignty through strengthening their governance systems.

The term consultation, then, refers to a legal obligation, and has less to do with motivations based on building the trusting relationships and reciprocity that are fundamental to reconciliation. For the purposes of this guideline, the guideline will focus and use engagement and mention consultation when the context refers to the legal obligation to consult.

1.3 Free, prior, and informed consent

Originally adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2007, Canada endorsed UNDRIP in 2016 and is currently in the early stages of implementing it through legislation like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act[9] and British Columbia’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.[10]

Within UNDRIP, is the principle of obtaining the free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) of communities before proceeding with projects that will impact them.[11] Appendix C has multiple learning resources, including resources on FPIC and its operationalization, which is the subject of much public discourse and will influence engineering projects.[12]

1.4 Safety, security, and benefit to Indigenous women and girls

For engineers and engineering firms serving the resource-extraction and development industries, actions recommended in Section 13 of the MMIWG Calls for Justice demonstrate how the engineering profession’s obligation to hold paramount public safety,[13] in this context, should be viewed to include marginalized and at-risk groups. Notably, Call for Justice 13.1 states:

We call upon all resource-extraction and development industries to consider the safety and security of Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people, as well as their equitable benefit from development, at all stages of project planning, assessment, implementation, management, and monitoring.

2 Using the Guideline

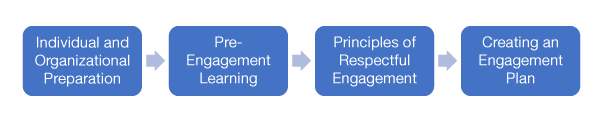

This guideline has been written for engineers and engineering firms who interact with Indigenous communities to provide guidance in preparing for and planning engagement that observes Indigenous protocols and meets the project and community’s needs. This guideline presents common principles that underlie successful engagement. It covers the content illustrated below.

This guideline is not a legal opinion and does not offer guidance on whether a project triggers the Crown’s duty to consult. Please refer to Appendix B for more on the Duty to Consult. Developed through engagement with engineering stakeholders and Indigenous community members, the intent of the guideline is to highlight the motivations and required preparation to conduct meaningful engagement along with practical principles to apply.

While some communities and organizations have established their own engagement protocols and best practices, some Indigenous communities and engineering stakeholders[iii] can use the guideline as the foundation for developing individualized engagement approaches or expectations.

Readers are encouraged to consider the following as they apply this guideline:

- This guideline is a living document. It will evolve as relationships are developed and as policies such as UNDRIP and collective responses to the TRC Calls to Action and the MMIWG Calls for Justice emerge.

- This guideline supports a learning journey. It is written for users with a range of experience levels. The content may create discomfort, so engaging with humility, empathy, an open mind, and sincerity is important. This will allow users to learn from missteps, gaining experience and confidence as they progress.

- Examples are potential starting points. Where possible, the engagement principles of the guideline will be illustrated through quotes provided by the engineering stakeholders and Indigenous community members who contributed to the guideline development process through virtual gatherings and surveys. These experienced and diverse perspectives will be identified as Engagement Insights. When interpreting examples, it is critical for guideline users to recognize that there is not one single Indigenous experience that represents all Indigenous Peoples’ perspectives or cultures.

- The context of words is important. Terms relating to Indigenous engagement are described in the glossary found in Appendix A. Some of these terms may have specific meanings in the context of Indigenous engagement. Due to the diversity of Indigenous cultures and types of Indigenous groups[14] engineers will engage with, the guideline will refer to all Indigenous groups[iv] as communities.

When applying the principles in this guideline, a user may encounter competing imperatives between project expectations and the Indigenous communities’ priorities. While each context will differ, engineers will need to steward project design preferences and client expectations with public safety and what the community identifies as in their best interest. This often places the engineer in the challenging position of advocating for appropriate process and resources because engagement practices that seek to address systemic injustice facing communities are often not specifically required. Engagement practices may need to extend beyond strict legal obligations to meet the engineer’s moral and ethical obligations.

3. Individual and Organizational Preparation

A foundational knowledge in Indigenous history, cultures, and the on-going effects of settler colonialism is a key component of successful engagement that will assist engineers in developing authentic and respectful relationships with Indigenous communities. It is highly recommended that project teams undertake Indigenous relations and intercultural training.

3.1 What engineers need to know

The training and preparation necessary will vary depending on the existing team competencies and individual experience. Individual and organizational preparation before engaging should include:

- Defining your individual positionality, which refers to the social and political contexts that shape your identity and influences your outlook and worldview. Reflect on the following questions influence your work as an engineer.:

- Where were you born and raised?

- On whose traditional territory do you live and work?

- How is your culture represented where you live?

- Are you free to observe and practice your spirituality?

- What other privileges do you enjoy?

- Becoming conscious of your positionality, influence, and responsibilities as engineers and members of society can elicit strong emotions, particularly at moments when you feel your core self-concept is being challenged. Depending on your positionality, familiarizing yourself with the concepts of white fragility[15] and settler fragility may help you better understand such reactions.

- Developing intercultural competence, which encompasses an understanding of how cultures are expressed and having the ability to work and communicate effectively with other cultures.

- Increasing bias awareness, recognizing that our biases can influence our assessment of the engagement process and the need to see the engagement process through different lenses.

- Learning about settler colonial history, including exposure to RCAP, the TRC Calls to Action, and the MMIWG Calls for Justice because they all represent extensive engagement with Indigenous people.

- Understanding how to incorporate trauma-informed engagement practices, which is a process of engaging with people who have experienced trauma.[16]

Expect the above preparations and reflections to stir strong emotions and challenge some of your biases. While potentially uncomfortable, embrace the process and bring others along with you. Decolonization requires an honest examination of political, legal, and societal norms that maintain settler control over Indigenous land and resources and continue to suppress Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. Decolonization is not a singular event, but a journey of learning, reflecting, and action.

As organizations learn and begin to develop respectful engagement practices, the following considerations should be applied:

- Allyship: consider ways to advance reconciliation through other business practices such as recruitment and hiring, community capacity building, and community project involvement.

- Offloading responsibility: Not all Indigenous consultants or staff will want to be the educator in this space, which is a common request during this important organizational training.

There are multiple ways to prepare and build organizational competencies. Appendix C has a list of learning formats and resources to assist individuals and firms to start the learning process, and there are many other resources available online.

While the above topics are foundational to practitioners working in this space, exposure to Indigenous art, literature and stories, and music will enrich the guideline user’s journey. Unfortunately, it is common to view Indigenous history as traumatic without celebrating the resiliency and beauty contained within Indigenous communities. Appendix C provides sources the reader can explore.

3.2 Who needs the preparation and training

The TRC Calls to Action #57 and #92 call upon governments and the corporate sector to educate public servants, management, and staff[17]:

on the history of Aboriginal peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal–Crown relations. This will require skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism.

Call to Action #92[18] also calls upon the corporate sector to adopt UNDRIP as a framework for reconciliation. This requires a proficiency in terminology and understanding. It is recommended that all staff obtain a base level of history and intercultural competency training.

4. Pre-Engagement Learning

4.1 Determine what community to engage

The Indigenous traditional territory of one community may overlap with other communities. Determining who to engage with and in what order can be challenging. This is especially true for projects that have the potential to impact one or more Indigenous communities.

Identification of communities with established or asserted Aboriginal rights or title may be required, and these include treaties, court decisions, litigation files, and existing treaty negotiation “statements of intent.” The proximity of a communities to a project is not necessarily a good indicator of who to engage with because many communities practice rights-based activities in areas far from their home reserve. Many communities were moved from their original territories as reserves were created under the Indian Act and treaty agreements. It will be the responsibility of the Crown to determine whether the duty to consult is triggered. Appendix B has information and links to assist identifying communities with Aboriginal rights.

4.2 Pre-Engagement Learning Considerations

Learning about a community before you reach out to them shows respect, reduces the burden of engagement on the community, increases your ability to build trust, and improves the possibility of community involvement in the project. Before you engage with communities, consider the following:

- History: Are there experiences in the community’s history that may influence their response to the project?

- Plans: What are the community’s aspirations and future plans? What opportunities or challenges might your project introduce for the community? Not all Indigenous communities publicize their community plans, in which case you will learn this once you engage with them.

- Protocols: How can you show respect through your interactions? Learning about the community’s culture is a sign of respect. This includes their protocols, which is the respectful way one interacts with Indigenous people according to their customs.

- Timing: Are there times of year where the community is engaged in practices like hunting, fishing, or berry-picking that may impact their ability to participate in engagement? How does your project timeline align with plans and practices in the community?

- Adequacy: Have you done enough preparation and learning to reduce the burden placed on the community to teach outside engineers about their history and culture? This could result in choosing a trauma-informed engagement process.

- Competency: Consider external consultants who specialize in Indigenous engagement and relations as you and your organization acquire experience and develop you own practice policy or strategies. This can be particularly important where jurisdictions overlap, or projects may adversely impact communities.

What you learn should influence your engagement plan. How and when you engage will reflect what you learned about the community’s values, aspirations, protocols, and previous project experiences. The pre-engagement learning may identify potential opportunities for the community’s participation, not only in the engagement process, but also in the project delivery- in this situation, early engagement is critical.

4.3 Sources for pre-engagement learning

Sources for pre-engagement learning vary, but consistent ways to learn about a community include community websites, federal, provincial, and territorial databases, and through direct communications with the community.

Part of one’s learning should be to prepare a land acknowledgement specific to the territory and community involved. Land acknowledgements can be a way to express one’s gratitude for the original stewards of the land and should reflect the speaker’s relationship to the land. Seek guidance on this process through resources or a workshop. The aim should be to avoid a gesture that is performative or insincere, and instead develop one that looks to authentically, meaningfully acknowledge the land, its people, and relationships to the land.

Appendix C has more information on what types of details the pre-engagement learning sources can provide and land acknowledgement links.

5. Principles of Respectful Engagement

Principles of respectful engagement apply to all types of projects and relationships between engineers, engineering firms, and Indigenous communities. Approaches will vary due to the scale of project, impacts on community, previous relationships, and individual goals and values of the community. Where appropriate, examples of approaches taken will be used to highlight engagement principles.

5.1 Build trust before projects

Trust is foundational to successful engagements and projects. Engagement is not a one-time conversation; it is a continuous process that builds trust and strengthens relationships.

Here are some ways to build trust over time:

- Begin early and avoid rushing: Building the relationship takes time. Many aspects of engagement rely on mutual trust that is best built over time. Trying to rush this process can erode trust. If possible, try to include time during community visits that are not strictly about advancing project business.

- Spend time together, ideally in the community. This is a more effective way to build the relationship than phone calls and emails.

- Attend events: Some community events are open to the public and attending can help you learn about the community’s culture and values. To be invited to some ceremonies is a great honour and declining can be disrespectful. If you accept an invitation, ask about protocols so you can be prepared.

- Observe protocols: Take the time to learn and observe community protocols which includes gifts and ways of interacting with Elders. (See Section 5.5).

- Be prepared to share: Be prepared to share a bit about yourself. Many Indigenous cultures’ introductions include details like your name, where you are from, and who your family is. For some communities this is a cultural protocol.

- Eat together: Sharing a meal with members of the community is a good way to let people get to know you and for you to meet people. Allocate the time for this and offer to provide the meal as a kind gesture.

- Involve the community: Seek ways to involve the community in the project in all ways that support their other goals. Viewing the community as a partner goes a long way to building trust.

- Respect contributions: Engagement that includes community contributions to design, beyond consulting services, demonstrates a commitment to learn from community members, Knowledge Keepers, or Elders.

- Continuity: Maintaining staff throughout a project is advisable because of the importance of personal relationships. If personnel need to change and new relationships need to be established, ensure that staff are informed on the work to date in order to respect the contributions of the community up to that point.

5.2 Engage early to maximize community involvement

Early engagement is critical to enabling participation by the community in the engagement process and project delivery. Seeking opportunities for community participation began in pre-engagement learning, but during the engagement process, specific project roles and contributions beyond participating in the engagement process can be explored with the community that include but are not limited to:

- Contributing local professional services and Traditional Knowledge.

- Contributing to the engagement facilitation and project monitoring.

- Contracting or subcontracting components of the project.

- Providing skilled and general labour on the project.

- Providing project materials, supplies, and equipment.

- Providing local accommodations and catering.

Ensure there is a clear understanding of the community’s capacity to fulfill these roles, along with contingency plans to ensure their success in the project delivery.

Not all communities have the in-house staff to review project documents or have existing capacity to contribute in the ways listed above. Developing the required capacity takes time and therefore engagement should occur as early as possible because opportunities and benefits can be lost if there is not sufficient time for a community to plan and prepare to participate.

Consider enabling on-the-job training, apprenticeship placements, and job shadowing opportunities that provide experience and employment to community members. These take time to establish with contractors, subcontractors, and members of the project team, but they are examples of providing benefits of projects beyond the engineering objectives themselves.

5.3 Resource engagement to meet the project and community’s needs

Begin by learning the community’s desired level of engagement and capacity to participate. The engagement and overall project timelines may not match the community’s capacity to contribute, even if they wish to. Keep this in mind as you establish preliminary project schedules and be prepared to accommodate or work with the community to find a balance between their capacity and the project objectives.

To estimate the timeframe needed for engagement, it helps to estimate:

- roughly how many community visits are needed.

- the time required to respond to inquires from both the community and from the design team.

- the time needed for the community to do any internal engagement and decision making.

Seek feedback on your developing engagement plan to ensure it aligns with the community’s capacity and adjust the timeframe to accommodate. The timing and resource considerations are different depending on the project, the level of collaboration, and the role the engineer has with the Indigenous community. Community initiated project RFPs may contain specific expectations for engagement while external proponents will need to determine the engagement timing and scope.

Engagement relies on establishing relationships. Therefore, as your network of contacts grows within a community and as you establish credibility and trust, the time needed to proceed through various stages of engagement can decrease with a community. The diversity of communities will always add uncertainty to estimating time and budget, but commonalities will emerge based on your experience.

5.4 Establish and maintain effective communication

Developing a consistent communication with one or more members of the community will be necessary. The community-assigned contact person or project liaison will be identified if you are responding to an RFP, but if your client is not the community, you can find the appropriate person several ways:

- The community website: most community websites provide contact information for various departments.

- Use the community’s general telephone number or email address. When seeking information for the first time, a phone call may be the best approach until you have connected with the person responsible for receiving inquiries and requests for engagement.

- Ask colleagues who have connections in the community but recognize that this should not be delegated to Indigenous colleagues by default. Consider developing a policy that includes compensation if Indigenous colleagues will serve this role. Relationships are everything, and as you conduct projects with Indigenous communities you will find that networks exist between communities that will assist you in the future.

Maintain communications while staying flexible

Communication and trust are a pair. Communications are an important way to establish trust with your community partners. Effective methods to establish and maintaining consistency, transparency, and accountability are:

- Adapt to preferences in both the way to correspond and their frequency. Don’t assume that emails are being read and follow up with a phone call. Some people may prefer the telephone – this is particularly true for some Elders.

- Maintain records as these can be part of other formal jurisdictional consultation requirements. Keep a log of meetings, phone calls, visits, and new contacts you make in community. For larger engagement programs it may be useful to use stakeholder management software to maintain a Record of Consultation.

- Take notes at meetings and share them with attendees. These should include action items and those assigned to tasks.

- Record direction given by community representatives and any commitments you make.

- Be responsive by following up on community questions.

- Deliver on commitments and if you cannot, be sure to explain why.

- Be transparent about your decision making/or your process

- Designate someone in your organization to handle regular communications. Having a consistent and accessible person for community representatives to contact will streamline communications both directions.

- Maintain connection after a project or between projects. Staying connected through periodic communications that doesn’t necessarily refer to a project demonstrates a less-transactional mindset and a commitment to community beyond contractual limits.

Procurement documents may outline initial communication expectations, but this will evolve as the project progresses.

Crafted for the community

When planning engagement sessions or meeting with community representatives, consider who will be at the gathering and how best to communicate with them. The following considerations relate to many Indigenous communities and will impact your ability to communicate project details, connect on a human level, and show intercultural respect:

- Communication effectiveness includes more than what you say, but also the types of materials you share, the technical terminology you use, your body language, and how you present yourself.

- Follow community protocols. These include but are not limited to introductions and the order of speakers.

- Use the community’s preferred name. Growing self-determination and the re-establishing of cultural protocols has also included some nations and communities adopting Indigenous names. Using outdated, Crown-assigned names is a sign of disrespect. An example resource is the British Columbia First Nations Pronunciation Guide.

- Silence can be important and does not necessarily signal agreement. Be patient and leave space for silence rather than filling it immediately.

- Know your audience. Be prepared with materials and methods that will be received by your audience. Examples include choosing between PowerPoint, handouts, visual aids, and oral presentations to communicate the project details. Match the terminology you use with your audience to ensure your message is understood.

- Be prepared to pivot or adjust. For example, be prepared for unexpected community attendance.

5.5 Observe community protocols to demonstrate respect

When working with Indigenous communities, observing protocols demonstrate respect for the community’s culture and traditional ways of being. Protocols vary among Indigenous cultures and sometimes between communities of the same nation. Learning about a community’s protocols may provide a challenge, as they are unlikely found listed online. Respectfully asking the community contact person is best. Some examples of Indigenous protocols you may encounter include:

- Land acknowledgements.

- Talking circles.

- Interacting with Elders or Knowledge Keepers.

- Feasts and gifting.

- Protocols specific to ceremonies such as smudges and pow wows.

Unfamiliarity with protocols can be intimidating, and mistakes may happen as one applies what they learn. View this as part of the learning journey, acknowledge your mistakes, and take forward what you learn.

There are important aspects of Indigenous cultures that engineers will likely encounter, and while it’s important to avoid treating all Indigenous communities as being the same, the following are a few considerations to prepare for:

Community spirituality and values:

- Not all communities practice and observe Indigenous spirituality. For example, some communities are predominantly Christian while others follow Indigenous worldviews. It is best not to make assumptions.

- Communities may incorporate their cultural teachings and value systems into their governance, economic, and business practices. An example could be planning on a longer timeframe than industry because of consideration given to past and future generations. Longer timeframes might also be required for internal dialogue and engagement among the community.

- Community values might be at odds with project objectives. Recognizing the source of resistance or disagreement is an important part of engagement.

- Many communities have a connection to the land that differs from western worldviews which can view land as an object to own or control. For example, land and resources may not necessarily be viewed by communities as assets, but as relations. Intercultural competency will assist engineers in respectfully navigating differing world views that impact projects.

- When there is a death in the community, it is common for the band office, businesses, and schools close for the day or days to support community members. Remain flexible and respectful should this impact your engagement process. When intergenerational trauma contributes to a community member’s death, this may be particularly sensitive for a community.

Traditional knowledge and Knowledge Keepers:

- There is no universal definition for Indigenous traditional knowledge because it varies between communities. However, unlike western notions of knowledge and intellectual property, Indigenous traditional knowledge is location specific, reflects the distinct cultures that passed it on from generation to generation, and remains in the control of Indigenous people.[v]

- Elders are recognized and esteemed members of communities who are keepers of traditional knowledge and are often included in community processes.

- Knowledge Keepers are not necessarily Elders, but also hold and care for traditional knowledge.

- Seek guidance from your community contact as to whether an engagement event or the process should include an Elder(s) or Knowledge Keeper(s), what their role will be, if there is a protocol for asking them to attend, and what an appropriate honorarium is for the event. For example, it is common for an Elder to open a gathering with a prayer or ceremony and for some communities an offering of tobacco is made along with an honorarium. Appendix C has links to helpful resources, including working with Elders.

Cultural appropriation, Indigenous languages, and use of Indigenous knowledge:

- As you incorporate aspects of a community’s culture, be mindful of historic practices that take cultural artifacts or practices without permission or compensation. It is always safer to ask with sincerity and take the community’s lead.

- Demonstrate respect by using a community’s language. This can be an effective way to demonstrate one’s respect and an effective way to communicate engagement outcomes and findings. While rare, this may be critical when working with Elders who speak English as a second language. If necessary, find out who in the community can assist your engagement team with translations.

- Be as specific as possible when referring to a community. For example, it is technically correct to refer to community members as “Indigenous,” but it is best to use the community’s preferred name.

- Community data, including traditional knowledge shared, is not the property of outside parties. Extractive practices have historically left communities with little influence on how their data and knowledge is used, shared, and profited from. See Appendix C for a link to an Indigenous data policy called the First Nations Principles of OCAP® (ownership, control, access, and possession).

6 Creating an Engagement Plan

Effective pre-engagement learning will prepare you to begin creating your engagement plan. Developing an engagement plan will require taking what you’ve learned from pre-engagement learning, what you know about timing considerations, communication methods, and community protocols, and balancing that with what you learn from initial conversations with the community.

6.1 Key engagement plan components

The community-focused engagement plan can be drafted based on the preliminary engagement plan and from input from the community. Key engagement aspects to include are:

- Engagement objectives

- Preliminary considerations

- Resourcing engagement

- Engagement timeframe

- Community engagement participants

- Format of engagement based on objectives and community capacity

- Engagement outcomes and how to evaluate effectiveness of engagement

Establishing an engagement plan early in the project poses a challenge because the level of effort required to engage respectfully is not known with certainty at the outset. When responding to a community infrastructure RFP, the engineers will have to apply judgement to many of the key engagement aspects.

6.2 Engagement plan objectives

It is critical that you understand how the community’s input will be incorporated into the project. Creating transparent expectations and following through will build trust. The following considerations relate to the level of influence the community will have and/or wants to have on the project:

- Determine the level of influence the community will have. Outside of legal obligations, this will depend on the type of project, engineering constraints such as codes and standards, the project timeline, the project budget, and the community’s capacity and desire to participate. For example, very time sensitive projects may only include high-level community input compared to projects where the community expresses a desire to contribute more time and expertise, and thus have more influence.

- Expected level of influence. The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) Spectrum of Public Participation[19] can help identify and communicate the level of influence community members and representatives will have as part of the engagement process. Expect to be held accountable for implementing community input at the level of influence established.

- Maintain transparency during engagement. Withholding information can come back to hurt your credibility and will erode trust you’ve built. Ensure you have communicated design details and have community approval prior to finalizing funding applications.

6.3 Preliminary engagement considerations

Your preliminary engagement plan is contingent on feedback from the community and will be influenced by the following questions, some of which you will have learned about in your pre-engagement learning and others from conversations with the community contact person:

- What communities to involve and are there overlapping traditional territories?

- Does the scope of the project change the number of communities to engage?

- What type of relationship does the engineer/firm and the community have, what is the type of project, and how do these influence the timing of engagement?

- Will the project impact the community in such a way to trigger the duty to consult?

- Who needs to be involved from the community: Chief and Council, hereditary leadership, and/or broader community members?

- Do government-to-government relationships influence any aspects of the engagement process?

- Is there a historical reason the community could be strongly supportive or resistant to consultation and engagement?

- Are there previous or ongoing projects that can impact a community’s capacity to engage and participate in the project delivery?

- How can early engagement enable community participation in the delivery of the project?

- You already know who the contact person is in the community from pre-engagement preparation. Now ensure you’re not missing other rights holders or interested parties. As examples, is there a form of traditional leadership, such as Hereditary leadership,[20] that should be invited to participate and are all clans or families appropriately represented?

- Are there community politics that could impact engagement participation?

- Is the preliminary project timeline appropriate?

After initial introductions and after the project team has shared the objectives of the project, initial community feedback will influence the engagement plan. This is central to developing an engagement plan that is community-focused. Ask a lot of questions early through conversations or a survey to collect engagement preferences so the plan meets the project and community capacity and offers opportunities for the community to participate in the engagement and project delivery. The following are examples of what you should learn from initial meetings with the community:

- Capacity and desire. Establish how the community wants to engage. This may include who will represent the community from a leadership, technical, and cultural perspective. Keep in mind that apprehension or a lack of enthusiasm to participate can be due to, among other reasons, capacity, apathy or resistance to the project, or a mistrust based on previous unsatisfactory consultation and engagement processes.

- Participation in project delivery. In what ways can the community participate and benefit from project delivery. The capacity to participate may need to be developed to make this possible which requires lead time and resources to compensate community members.

- Additional insights that may influence the engagement process. These can be cultural, social, and political dynamics that can influence engagement timing, community involvement, and the inclusivity of the engagement process.

6.4 Resourcing engagement

As a first step, ensure your team has developed the appropriate competencies and have conducted pre-engagement learning. If you expect a depth of engagement that will require the interpretation of traditional knowledge or incorporate spiritual protocols, you may seek to bolster your team with a cultural advisor. Consider the following if seeking a cultural advisor:

- The advisor should have ties to the Indigenous community. This will help avoid harmful generalizations about Indigenous Peoples and maximize the specific expertise they bring.

- Cultural advisors bring specialized knowledge. They should be capable of interpreting or adding context to cultural information shared and incorporating more complex protocols.

- Cultural advisors may or may not be able to speak for a community, regardless of their relationship to the community or who commissions them to participate.

6.5 Engagement timing

Having a preliminary timeframe is helpful but be prepared to accommodate the community’s capacity to participate, which as outlined in Section 5.2 can be associated with engagement timing. Participation can be providing input and feedback on the project, but it can also involve contributing to the project delivery. Often a community is well situated to provide needed services on a project. In this way, the project benefits go beyond the infrastructure itself but contribute economically.

Indigenous communities are like all other communities in that the diversity within represents different perspectives and ambitions. Keep this in mind as you design your engagement plan. In some cases, you may need to allocate time for the community to come to its own position on a project. This may or may not be facilitated by your organization but recognize this potential phase of engagement. It is worth noting community leadership and election cycles which can disrupt the engagement process. If relevant, prepare for this within your timeframe.

6.6 Community engagement participants

Who you engage with will vary between projects and between communities. The type of project may necessitate specialized perspectives from the community, while the diversity among communities will influence who is included. Beyond the community contact person, other Rights Holders and stakeholders[vi] you may be instructed to invite into the engagement process include, but are not limited to:

- Broader community groups like Tribal Councils or treaty representatives

- Community leadership like the Chief and Band Council or hereditary leadership

- Administration such as Band Office Manager or Administrator

- Technical staff like infrastructure operators and maintainers

- Infrastructure end users and operators

- Indigenous Knowledge Keepers and/or Elders

- Community youth

- Volunteer organizations

- Other project stakeholders

Note that elected officials and community staff may be unable to participate on the proposed timeline. They are responsible for all community needs– not just your project.

6.7 Engagement Format

Engagement can take many forms and should match the desired engagement objectives, support the relationship building process, and foster intercultural learning. Materials and information should be shared in a way that is easily understood by the audience, in a format they prefer. In-person engagement is more effective for building relationships, but you may need to accommodate the community’s capacity and ensure your team has the required engagement skills- bring in specialists if necessary. Examples of engagement formats include:

- Individuals going for coffee

- Group meetings or workshops

- Community open houses

- Site visits and walks

- Gatherings over on-line virtual platforms

It is always important to be flexible and meet the community where they are at. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many communities-imposed restrictions on visitors which would require an adapted approach to relationship building and engagement. Understand and follow the community’s lead with respect to cultural protocols and health and safety policies.

6.8 Engagement outcomes and evaluation

The sharing of engagement summaries is important to maintaining transparency. Summaries or findings can be shared through a presentation or report, including:

- Main themes to emerge

- Methods used to facilitate discussion and collect input

- Who participated

- How it influenced the project

- Questions that required follow-up and the responses to the inquiries

Confirm with the community that you interpreted their input correctly and that you have a shared understanding. Ensure the findings are accessible to the appropriate people – this could require hard copies for people without internet access or computer skills.

Evaluating engagement as it takes place is critical to adapting to unexpected occurrences like lower or higher than expected participation, or unanticipated resistance to a project. It is possible that community input changes the engagement approach, and this requires flexibility.

Evaluation can also occur after the project is complete. Lessons learned should be reflected upon and incorporated into future training and engagement planning. Seeking feedback from engagement participants can offer different and valuable perspectives. This learning process leads to improved engagement best practices and demonstrates a willingness to respond to community input.

The engagement process for a specific project is best approached as part of the larger relationship building process that continues after the project is complete and should contain considerations on how to maintain communication with the community. This is fundamentally different than engagement practices that are transactional in nature and view projects as isolated and unrelated.

6.9 Engagement collaboration

Input from infrastructure operators and maintainers can be critical to long-term design suitability and operation. Seek operator input and hear the feedback they offer. Make efforts to incorporate their first-hand experience to optimize project effectiveness.

During the engagement process, local traditional knowledge may contribute to a more holistic understanding of the project site conditions and/or the community’s relationship to the proposed project location. This opportunity will only arise if Knowledge Keepers and/or Elders are invited to and supported in the engagement process. Differences may arise between community priorities and values and engineering design constraints. Identifying the difference between design preferences and engineering standards is important as the engineer seeks to find mutual understanding with community members and project managers. It is much more likely that design constraints can be communicated, and alternatives explored if there is a trusting relationship between engineers and community members.

7 Conclusion

Relationships are at the core of respectful Indigenous consultation and engagement. This guideline aspires to prepare engineers and engineering firms for this task through individual and organizational preparation, pre-engagement learning, important engagement principles and considerations, and engagement planning.

The development of this guideline has involved a relationship building process between the engineering profession and Indigenous communities that forms the foundation for the engagement principles outlined within. As the relationship develops, so too will engagement practices. This guideline will evolve as a living document through continued sharing and learning. The guideline user is encouraged to identify the difference between their legal obligations and their professional ethical responsibilities to conduct their work in the best interests of the communities above client or personal interests.

Additional resources and references are contained in the appendices, including a glossary of Indigenous consultation and engagement terms (Appendix A), duty to consult and federal, provincial, and territorial consultation and engagement frameworks (Appendix B), and learning, helpful, and pre-engagement resources (Appendix C), and reference citations (Appendix D).

8 Acknowledgements

This guideline is the result of input from many generous and passionate participants from all over what is now called Canada. Elder Norman Meade of Manigotagan, Manitoba was in attendance for all engagement gatherings leading to the drafting of the guideline and his contributions connected his Métis culture with the engineering and engagement principles being discussed. A sincere thank you to everyone involved.

Appendix A: Glossary

accommodation[21]: Balancing Aboriginal and Crown interests by avoiding or minimizing identified adverse effects on Treaty or Aboriginal rights. Accommodation can include putting conditions on project approvals, requiring project proponents to modify project proposal, delaying approval decision or denying project approval.

allyship[22]: The act of working towards dismantling oppressive spaces by educating others on the realities faced by marginalized groups.

band or Indian band[23]: These terms refer to the governing unit of some First Nation communities instituted by the Indian Act, 1876. Bands, as defined by the Indian Act, use common lands for which the legal title is vested in Her Majesty, have funds held for it by the federal government, and are declared a band by the Governor in Council for the purposes of the Indian Act. Not all First Nations use these terms and may use First Nation or Nation instead. It is always best to confirm.

the Crown[24]: A symbol that represent the state and its government. With respect to Indigenous consultation and engagement in Canada, the Crown is the provincial, territorial, or federal governments, whom have a fiduciary duty to safeguard the interests of Indigenous Peoples.

Colonialism[25]: The domination of a people by a foreign state. It involves political and economic subjugation by the controlling actor.

Comprehensive community plan (CCP)[26]: The community’s vision for their future which can set short, medium, and long-term goals as well as their roadmap to achieve them. CCPs typically provide information on community values, governance structure, land and resources, infrastructure development, social structure, education, health and their economy.

Cultural advisor[27]: A recognized member of the community who holds traditional knowledge and specializes is working with organizations to interpret and apply traditional knowledge.

decolonization[28]: The un-doing or unsettling of colonial power structures and restoring Indigenous practices and ways of being.

Elder[29]: The term “Elder” does not simply refer to elderly people in a community, but the respectful acknowledgement of their role in the community. They are recognized by the community as holders of traditional knowledge, cultural practices and wisdom. Therefore, their input is often sought on community projects, programming, and community decisions.

free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC)[30]: The rights of Indigenous Peoples to participate in decisions that impact their lands and resources. In the context of consultation and engagement, the Crown commits to obtaining FPIC before projects are approved.

Indian Act[31]: Originally passed in 1876, the Indian Act is a federal law that governs matters relating to Indian status, bands, and Indian reserves. This paternalistic piece of legislation authorizes the federal government to regulate and administer the daily affairs of registered Indians and reserve communities.

Indigenization[32]: The act of recognizing the validity of Indigenous worldviews and knowledge and identifying opportunities to express indigeneity.

Indigenous vs. Aboriginal vs. Indian[33]: There has been an evolution of the terminology used to refer to Indigenous people in what is now Canada. The term “Indian” should only be used within legal contexts associated only to First Nations people with Indian status under the Indian Act. Of currently used terms, this one should be avoided due to it’s link to colonial policies. The term “Aboriginal” was and is still used in legal and constitutional contexts. The term “Indigenous” refers collectively or individually to First Nations, Metis, and Inuit. It is the preferred term when one cannot use the specific name of a community or nation.

intercultural competence[34]: The understanding of what an intercultural society is and how to effectively communicate and work with people of other cultures.

Knowledge Keeper[35]: An Indigenous community member who holds and cares for traditional knowledge and teachings that have been passed down by an Elder or senior Knowledge Keeper in their community.

land code[36]: A comprehensive law created by a First Nation that replaces some Indian Act sections that relate to land management.

pan-Indianism and Pan-Indigenize: Assuming all Indigenous groups share spiritual beliefs and have common histories and aspirations.

positionality[37]: This refers to social and political contexts that shape your identity, which influences your outlook and worldview. For engineering consultants this would include understanding how a number of factors influence their degree of privilege and how bias can impact their professional practice.

privilege: The social, economic, and political advantages or rights given to dominant groups of people based on their gender, race, sexual orientation, social class, physical abilities etc. Privilege includes unearned social power granted to members of a dominant group by formal and informal institutions.

proponent: The organization proposing a project for review and approval that can include but is not limited to industry, Indigenous governments, municipalities, and private entities and individuals.

protocol[38]: The way one interacts with Indigenous people that respects and observes their traditional ways of being and ethic systems. Protocols vary between Indigenous cultures and even between communities.

settler fragility[39]: The difficulty or inability to talk about one’s unearned privilege of living on and benefiting from the on-going displacement of Indigenous people from their territories and the effects of settler colonialism.

stakeholder vs. rights holder: Stakeholders are any party with an interest in a project. Indigenous people are rights holders because of distinct Aboriginal rights contained in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

trauma-informed engagement: A process of engaging with people who have experienced trauma that recognizes trauma symptoms and acknowledges the impact trauma has had on participants.

treaty[40]: Treaties are agreements between Indigenous groups, the Government of Canada, and often provinces and territories that define the ongoing rights and obligations of all parties. There are historic treaties signed between 1701 and 1923 and modern treaties which began in 1975.

unceded land[41]: Lands that First Nations people never surrendered or legally signed away to the Crown or Government of Canada.

white fragility[42]: According to Robin DiAngelo, white fragility “is a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves. These moves include the outward display of emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and behaviors such as argumentation, silence, and leaving the stress-inducing situation. These behaviors, in turn, function to reinstate white racial equilibrium.”

white saviour complex[43]: When a white person attempts to help non-white people because only they can save others from their situation. Despite sincerely intentions, this serves their own needs and contributes to the false narrative that BIPOC people are powerless.

worldview[44]: One’s comprehensive conception or apprehension of the world is from a specific standpoint. This is frequently informed by cultural, societal, spiritual, experiential, and other factors. In the context of indigenous engagement, recognizing one’s own worldview and respecting others’ worldviews is foundational to mutual understanding, effective communicating, and intercultural collaboration.

Appendix B: Duty to Consult and Consultation Protocols

Duty to Consult

The Government of Canada has a duty to consult, and accommodate when appropriate, Indigenous Peoples when projects could impact established or asserted Aboriginal or treaty rights. The duty lies with the Crown, although portions of the process can be delegated to project proponents.

The consultation and accommodation should balance Aboriginal interests with other societal interests, relationships and positive outcomes for all partners. The consultation process should be:

- carried out in a timely, efficient and responsive manner

- transparent and predictable

- accessible, reasonable, flexible and fair

- founded in the principles of good faith, respect and reciprocal responsibility

- respectful of the uniqueness of First Nation, Métis and Inuit communities

- includes accommodation where appropriate

The Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) Aboriginal and Treaty Rights Information System (ATRIS) is a web-based information system that maps Indigenous communities and displays information pertaining to their potential or established Aboriginal or treaty rights. This is helpful when identifying communities that could be affected by a proposed project. The Consultation and Information Service (CIS) at CIRNAC provides information about the location and nature of established or asserted Aboriginal and Treaty rights to federal officials and other interested parties.

Existing Federal, Provincial and Territorial Consultation Protocols

CIRNAC supports federal departments and agencies in upholding the Government of Canada’s duty to consult. This involves providing guidelines, training, and other tools. There are some established consultation protocols between Indigenous groups and provincial and territorial governments that facilitate engagement, promote relationship building, and clarify the roles of and responsibilities of the parties involved. For more information on the duty to consult including guidelines and existing provincial and territorial consultation protocols, refer to the CIRNAC website.

Other examples of consultation and engagement resources:

- Indigenous consultations in Alberta

- Consulting with First Nations (British Columbia)

- Duty to consult with Aboriginal peoples in Ontario

- Government of Saskatchewan Proponent Handbook

Appendix C: Learning Resources

The following learning formats and resources offer guideline users a place to start their personal learning and ways to engage their organizations in the learning process.

Learning Formats:

- Personal introductory learning. Options include self-guided learning, online resources like massive open online courses (MOOCs), and in-person or online facilitated courses.

- Intercultural competency training specific to your team’s needs. This can include but is not limited to concepts of empathy, justice, decolonization, Indigenization, trauma-informed engagement practices, and Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

- Indigenous cultural awareness training that includes terminology, misconceptions and stereotypes of Indigenous people, exposure to Indigenous social and political structures, Indigenous legal orders, and the impacts of policies like the Indian Act and UNDRIP.

- Community mandated cultural training for consultants working in their territories.

- Individual and organizational learning can be normalized institutionally as part of Indigenous history month or part of National Day of Truth and Reconciliation

- reading lists and book clubs

- bring in guest speakers who can contextualize Indigenous experience

- leveraging existing relationships to collaborate beyond engineering projects

- Regulator mandated continuing education for engineering registrants. Professional development opportunities are offered by various provincial and territorial regulators.

Examples of individual learning resources:

Books on Indigenous-Canada history, politics, and engagement

- 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act by Bob Joseph

- Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-up Call by Arthur Manuel and Grand Chief Ronald M. Derrickson

- Weaving Two Worlds: Economic Reconciliation Between Indigenous Peoples and the Resource Sector by Christy Smith and Michael McPhie

- Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Metis & Inuit Issues In Canada by Chelsea Vowel

- My Conversations with Canadians by Lee Maracle

- Indigenomics: Taking a Seat at the Economic Table by Caron Anne Hilton

- Standoff: Why Reconciliation Fails Indigenous People and How to Fix It by Bruce McIvor

The Royal Alberta Museum has an excellent repository of resources including reading lists, films and documentaries, radio and podcasts, Indigenous language apps, and other online resources.

University of Alberta Indigenous Canada MOOC is a 12-lesson online course that explores the history and contemporary perspectives of Indigenous Peoples living in Canada, from an Indigenous perspective.

The following are pivotal public works of investigation, engagement, truth telling, and healing. They have influenced much of the building and rebuilding of relationships between Canada and Indigenous peoples.

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples: Report

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action and various reports

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Calls for Justice

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Example group learning courses:

- Four Winds & Associates training

- Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. training

- Four Seasons of Reconciliation Education

- KAIROS Blanket Exercise

- Manitoba Environmental Industries Association (MEIA) offers an Aboriginal Cultural Awareness and Engagement Workshop

Regulator-specific training resources:

- Truth and Reconciliation mandatory regulatory module from Engineers and Geoscientists BC (EGBC)

Helpful resources

Working With Elders by First Peoples Cultural Council

International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) Spectrum of Public Participation

Queen’s University Terminology Guide

Native Land Digital is an interactive, web-based map demonstrating Indigenous territories, languages, and treaties. This website provides an accessible entry point for people interested in learning about territories based on locations. Similarly, Whose Land is a web-based map and learning resource.

FPIC resource: The University of British Columbia Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre has a discussion series on implementing UNDRIP. Article 3 refers specifically to Operationalizing FPIC.

Indigenous data governance

Principles of respectful data governance can be obtained through the First Nations Information Governance Centre’s web-based course: the First Nations Principles of OCAP® (Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession).

Land acknowledgments

Many intercultural workshops are available specifically on land acknowledgements or are part of larger Indigenous competency training. Seek out a workshop in your region or find resources online like this from the University of Toronto.

Pre-Engagement Learning Resources

The intended outcome of your pre-engagement learning is to inform your engagement strategy on community details relevant to the project. The sources will provide varied results, depending on the community and the type of project. This preparation reduces the burden placed on the community or communities, but where gaps exist after this desk-top study, seek input from the community on further sources of information and specific details. influence your engagement plan and

The following are examples of learning resources and details they can provide:

| Sources of Learning | Available Information |

|---|---|

| Inquire with colleagues |

Previous projects with the community may produce valuable insights into future projects and/or inform you on who in the community to connect with Colleagues or your Indigenous relations team can be helpful in this respect |

| Community websites |

Information on past or current projects, treaty processes, or ongoing litigation Engagement protocols or contact information for protocol inquiries. In many communities this is called the Referrals Process Comprehensive community plans provide the community’s vision for their future including economic development plans, land use plans, environmental management plans, physical development plans, and many others |

| Federal government databases | Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) website has links to maps, community profiles, data and interactive tools relating to First Nations, Inuit and Metis people, treaties, and lands |

| Direct inquiries with the community | Where questions are left unanswered from the above approaches and you do not have a local contact, inquire with the community about further sources of information |

Appendix D: References

Antoine, Asma-na-hi, Rachel Mason, Roberta Mason, Sophia Palahicky, and Carmen Rodriguez de France. Pulling Together: A Guide for Curriculum Developers. BC campus, 2018. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationcurriculumdevelopers/chapter/respecting-protocols/.

Caldararu, Alexandru, Julie Clements, Rennais Gayle, Christina Hamer, and Maria MacMinn Varvos. Canadian Settlement in Action: History and Future. NorQuest College, 2021. https://doi.org/10.29173/oer24.

Canada, Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs. “Government of Canada and the Duty to Consult.” Administrative page. Government of Canada, March 15, 2012. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1331832510888/1609421255810.

Canada, Government of Canada; Indigenous Services. “First Nations Land Management.” Reference material. Government of Canada, February 25, 2022. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1327090675492/1611953585165.

Canada, Library and Archives. “Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples,” October 4, 2016. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/aboriginal-heritage/royal-commission-aboriginal-peoples/Pages/final-report.aspx.

CTLT Indigenous Initiatives. “Positionality & Intersectionality.” UBC CTLT Indigenous Initiatives. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://indigenousinitiatives.ctlt.ubc.ca/classroom-climate/positionality-and-intersectionality/.

Crey, Karrmen. “Bands.” UBC Indigenous Foundations, 2009. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/bands/.

Danesh, Roshan, and Robert McPhee. “Operationalizing Indigenous Consent through Land-Use Planning,” n.d.

DiAngelo, Robin. “White Fragility.” International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 3 (3) (2011): 54–70.

“EDI Glossary,” Vice-President Finance & Operations Portfolio. University of British Columbia. Accessed June 22, 2022. https://vpfo.ubc.ca/edi/edi-resources/edi-glossary/#p.

Engineers Canada. “Public Guideline on the Code of Ethics.” Engineers Canada, March 2016. https://engineerscanada.ca/publications/public-guideline-on-the-code-of-ethics.

Hanson, Erin. “The Indian Act.” UBC Indigenous Foundations, 2009. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/the_indian_act/.

Parliament of Canada. “Government Bill (House of Commons) C-15 (43-2) - Royal Assent - United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act - Parliament of Canada,” June 6, 2021. https://parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-2/bill/C-15/royal-assent.

Government of Canada. “Comprehensive Community Planning.” Abstract; contact information; promotional material, November 3, 2008. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1100100021901/1613674678125#sec2.

Government of Canada Crown-Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. “Treaties and Agreements.” Administrative page. Government of Canada, July 30, 2020. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028574/1529354437231.

Harris, Carolyn, and Andrew McIntosh. “Crown.” Canadian Encyclopedia, July 26, 2021. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/crown.

Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. “Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls: Calls for Justice,” 2019. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Calls_for_Justice.pdf.

International Association for Public Participation. “Public Participation Pillars.” International Association for Public Participation. Accessed February 4, 2022. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/communications/11x17_p2_pillars_brochure_20.pdf.

Joseph, Bob. “Meaningful Consultation with Indigenous Peoples.” Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., September 24, 2018. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/meaningful-consultation-with-indigenous-peoples.

Joseph, Bob. “Hereditary Chiefs versus Elected Chiefs.” Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., May 17, 2021. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/the-difference-between-hereditary-chiefs-and-elected-chiefs.

Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. “Colonialism.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, May 20, 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/colonialism.

Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. “Worldview.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, November 16, 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/worldview.

Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation. “Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act - Province of British Columbia.” Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. Province of British Columbia. Accessed February 1, 2022. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/indigenous-people/new-relationship/united-nations-declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.

Parrott, and Michelle Filice. “Indigenous Peoples in Canada.” Canadian Encyclopedia, October 4, 2021. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/aboriginal-people.

Province of British Columbia. “Guide to Involving Proponents When Consulting Firsts Nations.” Province of British Columbia, 2014. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/natural-resource-stewardship/consulting-with-first-nations/first-nations/involving_proponents_guide_when_consulting_with_first_nations.pdf.

Queen’s University. “Being an Ally to Indigenous People.” Office of Indigenous Initiatives, 2022. https://www.queensu.ca/indigenous/decolonizing-and-indigenizing/being-ally.

Queen’s University. “Decolonization and Indigenizing.” Office of Indigenous Initiatives, 2022. https://www.queensu.ca/indigenous/decolonizing-and-indigenizing/defintions.

Queen’s University. “Elders, Knowledge Keepers, Cultural Advisors.” Office of Indigenous Initiatives, 2022. https://www.queensu.ca/indigenous/ways-knowing/elders-knowledge-keepers-and-cultural-advisors.

Queen’s University. “Terminology Guide.” Office of Indigenous Initiatives, 2022. https://www.queensu.ca/indigenous/ways-knowing/terminology-guide.

Robart, Kate. “Impact Over Intent: Issues with the ‘White Saviour’ Complex.” The Athenaeum (blog), March 14, 2021. https://theath.ca/features/impact-over-intent-issues-with-the-white-saviour-complex/.

SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. “SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, July 2014. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4884.pdf.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. “Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.” Winnipeg, Canada: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf.

“Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.” Winnipeg, Canada: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf.

UN General Assembly. “United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Resolution / Adopted by the General Assembly.” United Nations Global Compact, October 2, 2007. https://www.refworld.org/docid/471355a82.html.

Watson, Kaitlyn, and Sandra Jeppesen. “SETTLER FRAGILITY: Four Paradoxes of Decolonizing Research.” Revista de Comunicação Dialógica, March 2, 2021, 78–109. https://doi.org/10.12957/rcd.2020.55392.

Wilson, Kory, and Colleen Hodgson. Pulling Together: Foundations Guide. Victoria, BC: BCcampus, 2018. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationfoundations/back-matter/glossary-of-terms/.

Endnotes

[i] The term “Aboriginal” is used in legal and historical contexts. See Appendix A Glossary for the difference between the terms Indigenous, Aboriginal, and Indian.

[ii] The duty to consult, and in some cases accommodate, was born out of Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 and made legally required through numerous Supreme Court of Canada challenges. While a Crown responsibility, the duty can be delegated to other parties in some situations. See Appendix B for more on the duty to consult.

[iii] Other users will find the principles herein valuable whether they be researchers, contractors, or academic institutions.

[iv] Indigenous people form numerous types of groups which can be involved in the engagement process or be a source of information. Examples of these different groups include a First Nation, Indian Band, Tribal Council, Inuit, or Metis Settlement. The guideline user should research what group(s) to engage with.

[v] Article 31 of UNDRIP outlines Indigenous Peoples’ right to maintain, control, and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.

[vi] While engineering community engagement typically involves seeking input and feedback from stakeholders, be mindful that Indigenous engagement often involves seeking input from people with Aboriginal rights and title. Rights holder is a more appropriate term to use in this situation.

[1] Engineers Canada, “Public Guideline on the Code of Ethics.”

[2] Canada, “Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.”

[3] “Calls to Action.”

[4] Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, “Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls: Calls for Justice.”

[5] UN General Assembly, “Refworld | United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

[6] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, “Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future.”

[7] Canada, “Government of Canada and the Duty to Consult.”

[8] Joseph, “Meaningful Consultation with Indigenous Peoples.”

[9] “United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.”

[10] Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation, “Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.”

[11] UN General Assembly, “Refworld | United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

[12] Danesh and McPhee, “Operationalizing Indigenous Consent through Land-Use Planning.”

[13] Engineers Canada, “Public Guideline on the Code of Ethics.”

[14] Parrott and Filice, “Indigenous Peoples in Canada.”

[15] DiAngelo, “White Fragility.”

[16] SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative, “SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach.”

[17] “Calls to Action.”

[18] “Calls to Action.”

[19] International Association for Public Participation, “Public Participation Pillars.”

[20] Joseph, “Hereditary Chiefs versus Elected Chiefs.”

[21] Province of British Columbia, “Guide to Involving Proponents When Consulting Firsts Nations.”

[22] Queen’s University, “Being an Ally to Indigenous People.”

[23] Crey, “Bands.”

[24] Harris and McIntosh, “Crown.”

[25] Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, “Colonialism.”

[26] Government of Canada, “Comprehensive Community Planning.”

[27] Queen’s University, “Elders, Knowledge Keepers, Cultural Advisors.”

[28] Queen’s University, “Decolonization and Indigenizing.”

[29] Queen’s University, “Elders, Knowledge Keepers, Cultural Advisors.”

[30] UN General Assembly, “Refworld | United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

[31] Hanson, “The Indian Act.”

[32] Queen’s University, “Decolonization and Indigenizing.”

[33] Queen’s University, “Terminology Guide.”

[34] Caldararu et al., Canadian Settlement in Action.

[35] Queen’s University, “Elders, Knowledge Keepers, Cultural Advisors.”

[36] Canada, “First Nations Land Management.”

[37] CTLT Indigenous Initiatives, “Positionality & Intersectionality.”

[38] Antoine et al., Respecting Protocols.

[39] Watson and Jeppesen, “SETTLER FRAGILITY.”