Notice

Disclaimer

Engineers Canada’s national guidelines and Engineers Canada papers were developed by engineers in collaboration with the provincial and territorial engineering regulators. They are intended to promote consistent practices across the country. They are not regulations or rules; they seek to define or explain discrete topics related to the practice and regulation of engineering in Canada.

The national guidelines and Engineers Canada papers do not establish a legal standard of care or conduct, and they do not include or constitute legal or professional advice.

In Canada, engineering is regulated under provincial and territorial law by the engineering regulators. The recommendations contained in the national guidelines and Engineers Canada papers may be adopted by the engineering regulators in whole, in part, or not at all. The ultimate authority regarding the propriety of any specific practice or course of conduct lies with the engineering regulator in the province or territory where the engineer works, or intends to work.

About this Engineers Canada paper

This national Engineers Canada paper was prepared by the Canadian Engineering Qualifications Board (CEQB) and provides guidance to regulators in consultation with them. Readers are encouraged to consult their regulators’ related engineering acts, regulations, and bylaws in conjunction with this Engineers Canada paper.

About Engineers Canada

Engineers Canada is the national organization of the provincial and territorial associations that regulate the practice of engineering in Canada and license the country's 295,000 members of the engineering profession.

About the Canadian Engineering Qualifications Board

CEQB is a committee of the Engineers Canada Board and is a volunteer-based organization that provides national leadership and recommendations to regulators on the practice of engineering in Canada. CEQB develops guidelines and Engineers Canada papers for regulators and the public that enable the assessment of engineering qualifications, facilitate the mobility of engineers, and foster excellence in engineering practice and regulation.

About Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

By its nature, engineering is a collaborative profession. Engineers collaborate with individuals from diverse backgrounds to fulfil their duties, tasks, and professional responsibilities. Although we collectively hold the responsibility of culture change, engineers are not expected to tackle these issues independently. Engineers can, and are encouraged to, seek out the expertise of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) professionals, as well as individuals who have expertise in culture change and justice.

In addition, it is important to keep in mind that the category of “women” in the context of workplace equity for women is diverse in itself. As such, a universal or “one-size-fits-all” approach is not be suitable as it does not account for the unique challenges that different groups of women may face. To learn more about diversity in engineering, please visit the following page.

1. Background

1.1 Context and rationale

Canada’s engineering workplaces continue to face a shortage of women engineers. Despite ongoing efforts on the part of many, and some positive indicators, progress for women in engineering remains slow, and representation rates remain low, currently below 15%.

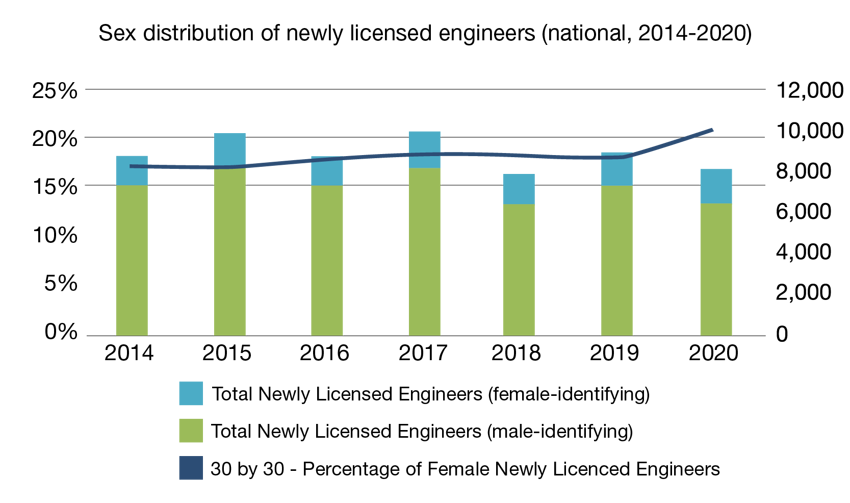

- In 2020, provincial and territorial engineering regulators reported to Engineers Canada that 14.2% of total national membership were female-identifying.[1]

- Just over one-fifth (20.6%) of newly licensed engineers in 2020 identified as women.

Engineers Canada is working to increase the representation of women within the engineering field. An objective of its 30 by 30 initiative is to raise the percentage of newly licensed engineers who are women to 30 per cent by the year 2030. The organization adopted a strategic 2019-2021 priority that builds on ‘30 by 30’ to focus on the recruitment, retention, and professional development of women in the engineering profession. Recognizing that 30 per cent is held as the tipping point for sustainable change, Engineers Canada maintains that achieving the related objectives will help drive cultural change in the engineering profession, supporting even greater involvement of women in the profession.[2]

Research shows that the work of the engineering profession will be enhanced by greater participation of women as organizations that are diverse, equitable and inclusive workplaces enjoy greater business success and have more positive impact. Beyond just ‘growing the counts’ of women, improving gender equity in the workplace will have positive benefits – the needs of society will be better met, the outcomes of employers and projects will be improved, and the day-to-day workplace experience will be enriched.[3]

1.2 Purpose and content of the guideline

The guideline was written primarily for engineers and engineering firms, but provides information and guidance that can also be used by individuals, employers, and other stakeholders across Canada for enhancing women’s participation in the engineering profession. Its intended outcome is that people within Canadian workplaces that employ engineers will have a deeper understanding of the challenges that impede women’s full participation and a clear sense of how to take action to address those challenges.

This guideline provides systematic approaches to addressing the challenges of workplace equity. It has been developed to complement, support, and amplify valuable initiatives that have been undertaken across the profession and in related organizations. It includes the following key steps in working towards achieving workplace equity for women:

- Collecting information within a workplace to take an evidence-based approach;

- Using established methods to analyze the information and develop well-reasoned conclusions;

- Creating priorities for action; and,

- Defining the inclusive practices and behaviours, the policies and programs, and the organizational culture changes that will make a difference for equity.

The appendices are composed of further background information and motivations for the focus on gender equity, a glossary, change agent tools and examples including case studies, and a curated list of resources for appropriate tools, credible engineering-relevant information sources, and guidance for further exploration. This guideline is intended to provide guidance to help individuals and employers to use the many resources and tools available for taking pragmatic action.

1.3 Using the guideline

Engineers Canada 2020 Survey results[*], as well as tips, recommendations, and examples for best practices are presented throughout sections 2-4. Resources included in this guideline and its appendices are meant to serve as a starting point. There are many other resources available online, and new insights and tools are being made available on a regular basis which readers are encouraged to consult.

Readers are also encouraged to consider the following as they use the guideline:

- Workplace equity concerns go beyond women. A focus on the challenges faced by women in engineering workplaces supports other important objectives related to inclusion across race, ethnicity, (dis)ability, age, sexual orientation, gender expression and other identities. Recent work emphasizing that identities are “intersectional” highlight this point – individuals have multiple and diverse identity factors (beyond gender) that intersect to shape their perspectives, ideologies, and experiences.

- Greater equity for women will result from both individual actions and employer initiatives. These are not mutually exclusive, but rather complementary and additive in impact.

- Engineers, managers, and leaders have a responsibility to not be bystanders. They should take accountability for being an ally, building their own understanding and skills, and influencing those around them to foster a positive, inclusive work environment where women can thrive.

- Employers can implement well-chosen actions for attracting, developing, and retaining women. Embedding gender considerations within core business concerns and people management practices involves re-thinking, disrupting, and re-designing the system where necessary.

2. Making evidence-based decisions

2.1 Initial assessments

In order to make meaningful change toward developing workplaces that are more inclusive of women, it is important to first “assess where your organization is now in terms of gender diversity and then you can decide where you want to go and how to get there.”[4]

The engineering profession is trusted to create solutions and has an obligation to protect the public. This first step supports an engineer’s professional responsibility to “distinguish between facts, assumptions, and opinions”. This is enshrined in multiple provincial Codes of Ethics for the engineering profession.[5] While these references in the Codes explicitly address technical engineering work, the principle of evidence-based decision-making is relevant to ‘taking stock’ on issues of gender inclusion. It is not intended to discount qualitative or experience-based input as individual perspectives can be valuable indicators of important issues to be explored. Basing discussions in evidence can resonate with decision-makers, engineering staff members, and others whose engagement in the process and commitment to taking action will be critical.

Initial assessments can:

- Encourage awareness, learning, and change;

- Ground discussions and actions in a shared view of the current situation;

- Focus efforts where the impact will be greatest; and,

- Define benchmarks of the current status, for tracking progress and adjusting approaches as needed.

It is best to start with core questions about the organization’s current situation and then examine how achieving greater equity for women could have an impact.

- Where are some ‘pain points’? What are people concerned about?

- What is most important to your organization’s potential success? (E.g., looking for more innovation, less turnover, specialized skills that are in short supply, stronger relationships with customers or stakeholders, etc.)

- Which topics will be most likely to generate some momentum and commitment to action on equity for women?

- What is the level of understanding across the organization of the various issue(s) related to gender diversity? (E.g., concerns, myths, or misconceptions that should be addressed.)

2.2 Data gathering

Data gathering (qualitative and quantitative) should be carefully planned, structured and undertaken, to safeguard privacy and not cause harm, but it does not need to be overly complex or difficult. The next few sections will provide alternatives to enable even the smallest organizations to collect relevant information through various types of measurements, set their targets and report results, based on their priorities.

Getting started can include the following:

- Look at comparable data available from published reports, industry associations, or your local employer network. Appendix D provides some example resources and guidelines.

- Re-purpose or adapt people-related measurements that are already in place in the organization. These might include applicant tracking data, workforce counts in various job categories, turnover rates, exit interviews or employee surveys.

- Generate a useful set of indicators through techniques[6] such as using recognized benchmarks; applying systematic methodologies for assessing workplace practices; and disaggregating data by gender and also its intersections[7] with racial identities, generation, disability, etc.

2.3 Three measurement approaches

Measurement is critically important in order to illuminate the ‘invisible problem’, dispel myths and misconceptions, and promote change. Well chosen measurements present a factual and compelling state of the organization that leads to further progress.

This section outlines three measurement approaches, looking at:

2.3.1 Inclusive practices and behaviours

- To what extent do people behave inclusively?

- How equitable are the organization’s people management practices (formal and informal)?

- Where are there gaps or opportunities for improvement?

Well-meaning statements of commitment are only a starting point; it is through day-to-day practices and behaviours that employers can address barriers for women and achieve sustainable equity. Assessing both the organizational policies and individuals’ behaviours will help to pinpoint the changes that will shift the experience of inclusion and women’s representation in the workplace.

When reviewing policies and practices, consider prioritizing revisions by answering the four core questions about the organization’s current situation (see section 2.1).

Assessing practices and individual behaviours could include the following:

- Comparing your own organization’s practices to recognized best practices for gender diversity and equity for women.

Tip: Resources listed in Appendix D can be used as a starting point. - The Global Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Benchmarks (GDEIB)[8], which is becoming a widely known tool for reviewing organizational practices that create and sustain an inclusive organization. With a comprehensive coverage that extends beyond gender, it presents 275 benchmarks in 15 categories, addressing aspects such as leadership, training, compensation practices, communication, and externally-facing services and relationships.

Tip: Gather a diverse panel of knowledgeable staff members to provide ratings. - The GBA Plus (Gender-Based Analysis Plus) methodology[9] developed by Women and Gender Equality (WAGE) Canada, which provides an analytical process to assess how women, men and non-binary individuals[†] may experience policies, programs and initiatives differently. The “Plus” refers to the importance of using an intersectional lens to recognize that identity characteristics such as age, race, geography, (dis)ability, family responsibilities and many others will have an impact.

Tip: The GBA Plus approach is particularly useful for checking assumptions and biases about an issue and its possible effects on different individuals. Relying on data and experience that primarily reflect men can miss important differences and have negative impacts.[10]

Any review of practices must go beyond the formal documentation. For example, there may be a defined process for staffing decisions that appears equitable, yet unconscious bias on the part of hiring managers can easily lead to inequitable results. Similarly, work-life balance policies will have little benefit for women with family responsibilities if the best project assignments only go to engineers who are available for long work hours.

2.3.2 Sense of inclusion

- Do women feel as though they belong and that their contributions are valued?

- Are the day-to-day workplace experiences of women and men comparable?

- Do differences arise when intersecting identity factors are considered? (E.g., what is the experience of racialized women, or women with children?)

There are many well-defined methodologies for understanding the workplace experience that will provide helpful examples of interview, focus group, and survey questions. The GBA Plus framework also provides tools with analytical questions that will help guide the interpretation of results.

Collecting and integrating both quantitative and qualitative data will yield the best insights and help to paint an accurate and compelling picture of the environment.

Qualitative information about workplace experiences can be gathered from sources such as:

- Confidential interviews or focus groups.

Tip: Semi-structured approaches in a psychologically safe atmosphere, often termed a ‘safe space’, will yield the best results. Conduct discussions separately with participants identifying as female, male, or non-binary. - Anonymized findings from HR practices such as exit interviews, harassment complaints, ‘stay’ interviews, promotion discussions, etc. that can illuminate individual experiences and concerns.

Tip: Focus on trends and patterns, using the individual examples as illustrations of the more general findings. - Questions and discussion topics that have been raised within the organization’s women’s network (if any), training sessions, or women-focused events.

Tip: Validate these inputs with a broader sample of women. - Comments made in employee engagement surveys.

Tip: Ensure that the comments can be analyzed separately by gender at a minimum, and ideally by other identity characteristics.

Quantitative information about workplace experiences can be gathered from sources such as:

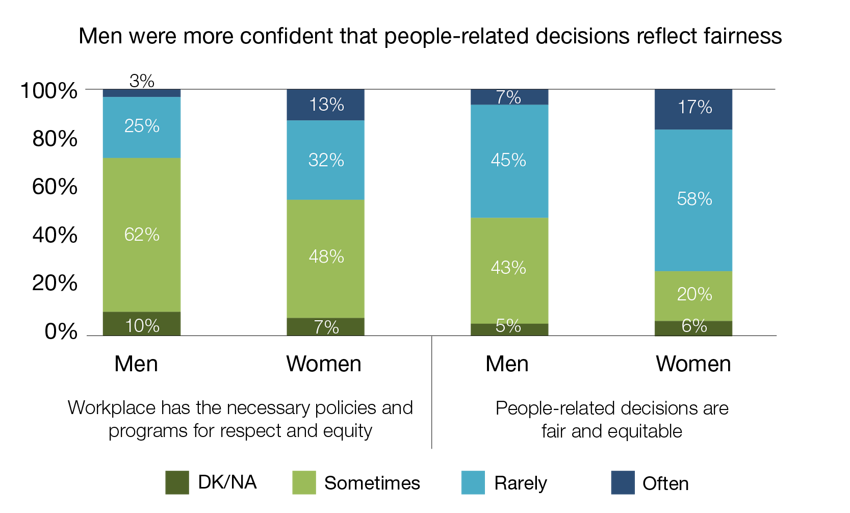

- Existing employee surveys that touch on topics such as engagement, satisfaction, career expectations, perceptions of fairness in HR practices, access to training and professional development, etc. In the Engineers Canada survey, women respondents were significantly less confident than men that people-related decisions are fair (see Figure 1).

Tip: Disaggregate the results by gender, as well as by other identity characteristics such as job tenure and classification, age, race, family status, (dis)ability, etc.

Figure 1: Gender differences in perceptions of fairness (Engineers Canada survey, 2020; N=688)

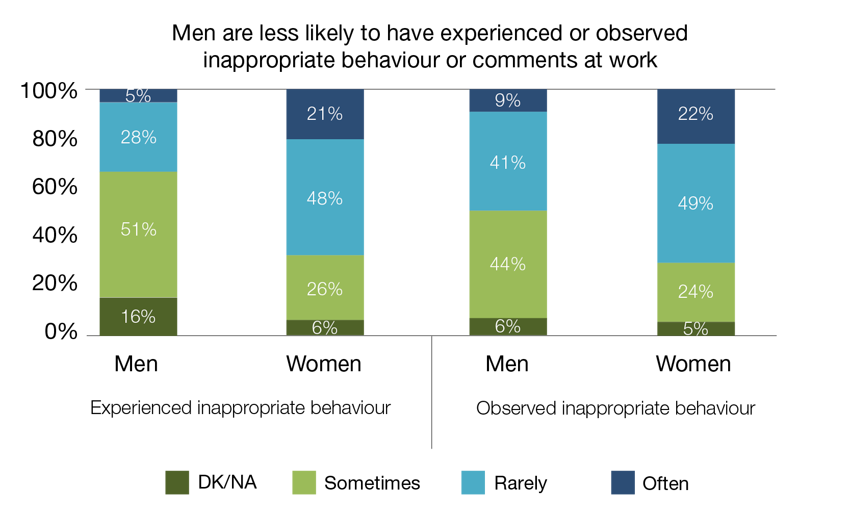

- Customized surveys that explore topics such as experiences of harassment and micro-aggressions, sense of being valued, assessment of leaders’ and managers’ commitment to gender equality, comfort with raising concerns, etc. For example, in the Engineers Canada survey, 2 of every 3 men said they rarely experience inappropriate behaviour or comments (or don’t know). Among women, 2 of every 3 said they sometimes or often experience them. (See Figure 2.)

Tip: Disaggregate the results by gender and other characteristics. If such surveys are new to the organization, a clear and consistent communications effort will be required to encourage candid responses from a large proportion of the workforce. Explain clearly the purpose of the initiative, how the data will be used, and how privacy will be assured. Provide contact names for any concerns that arise. Engage internal stakeholders and opinion leaders in reviewing and interpreting the results and implications.

Figure 2: Gender differences in workplace experiences (Engineers Canada survey, 2020; N=690)

- HR process data, such as recruitment success rates; special assignments and promotion rates; compensation levels (pay equity); performance and potential ratings; training participation; leaves; and turnover. Exploring for potential biases by looking at available data separated for those identifying as women, men or non-binary will be helpful in galvanizing support for changing practices.

Tip: Focus on one or two indicators and pursue those findings with interviews to help interpret results, explore potential root causes, and generate potential solutions.

2.3.3 Workforce demographics

- How well are women represented in various engineering roles and at various levels in the organization?

- How diverse is the population of women?

- What are the gender breakdowns at various career points such as recruitment, promotion, retention, and important learning opportunities?

The demographic representation of women in the engineering workplace can be seen as an outcome of the previous two measures (see sections 2.3.1 and 2.3.2).

The indicator that has received the most attention for women’s equity in engineering is their numbers. The 30 by 30 initiative, educational institutions, and many workplaces have set their own metrics and goals concerning the number of women in engineering. Well-chosen metrics of women’s representation can become powerful levers for change. They should align with the organization’s rationale and goals for increasing the presence of women in the workplace. If increasing gender diversity to better serve external clients is a central interest, then at least some of the focus should be on women’s representation within roles that can affect clients. If a particular skills shortage is a concern to the organization’s leadership, then recruitment and retention of women in that talent pool should be a core, visible metric.

Methodologies for examining the representation of women in an engineering workplace are helpful for decision-making – for making meaningful comparisons, understanding and targeting the key gaps, and tracking progress.

- Use comparative statistics to put a particular number in context. Data are available in published online resources and from engineering or industry associations. Engineers Canada, provincial and territorial regulators, professional women’s networks, industry associations, and consulting firms are all good sources. More refined breakdowns can be accessed through Statistics Canada’s online census data and occasionally in specific analytical reports.

Tip: Consider aspects such as geographic location, engineering discipline, and other constraints for comparability. Often there will not be a perfect match – construct an approximation from multiple indicators.

- Disaggregate the data to explore and prioritize any identified gaps in women’s representation.

Tip: Look for any differences in the numbers of women across job levels, tenure in the organization, racial identity, Indigenous identity, and other characteristics. For example, if the overall representation of women is high, yet there are few to none in senior roles, then retention, development and/or promotions may be the priority for action. If the numbers of newly hired racialized or newcomer women are low, then that may suggest a need for focused recruitment strategies.

- Use representation data with useful breakdowns to monitor the impact of actions taken by the organization.

Tip: Ensure that the counts being used for monitoring can realistically be expected to reflect any impact of the actions being taken. In an organization that ‘promotes from within’, new recruitment strategies will affect representation in entry-level positions but not within senior management. Investments to minimize unconscious bias in performance evaluations or remove unintended barriers to career development may have widespread impact. Some actions can be expected to generate early results, others may take years to show a significant impact.

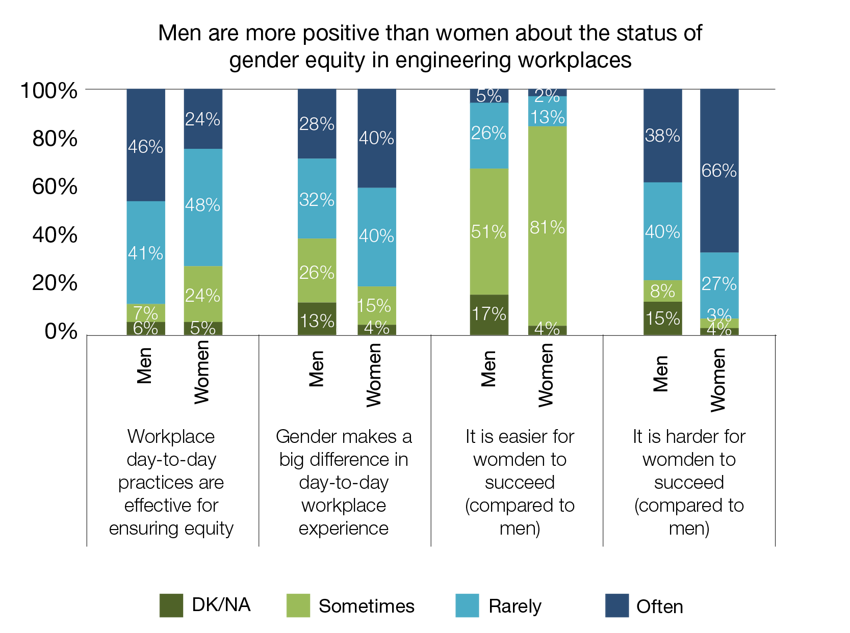

2.4 The power of measurement

The 2020 Engineers Canada survey of engineers and engineering workplaces has demonstrated some compelling differences between the perspectives of men and women. As shown in Figure 3, men hold a more positive view about the status of gender equity in their workplaces.[12] A lack of consensus on the current situation across the profession will be a barrier to making progress.

Figure 3: Gender differences in assessment of current levels of equity (Engineers Canada survey, 2020; N=690)

Well-defined and clearly communicated metrics reveal the gaps between ‘what is’ and ‘what ought to be’. They foster a sense of urgency and a commitment to action. The following chapter explores what those actions might include.

3. Actions for equity

Engineering workplaces are not the only, nor the first, to tackle the challenges of ensuring equity for women. Experiences and research across a range of industries, professions, and work environments have generated insights about successful practices.

To have the best impact, decision makers and change agents must be able to reflect the best of engineers’ problem-solving and design thinking capabilities:

- See the problem to be solved;

- Adopt a principles and science perspective;

- Educate themselves about equity issues and the gaps in the current state in order to design a fitting solution; and,

- Seek out and apply appropriate tools, knowledge resources and best practices.

Appendix C presents three brief examples that illustrate the measurement and action principles.

Individual workplaces will have their own priorities and areas of focus, based on their organizational realities and informed by the assessments they have undertaken. The systemic barrier that is selected as a focus might be one that encompasses the entire organization, or it might be specific to one division or occupation, or to one policy or a particular aspect of workplace behaviour. There is no one solution that fits all situations.

A list of research resources and evidence-based practices has been provided in Appendix D. Actions can be built upon themes such as the following:

| Action theme | Characteristics | Sample successful practices |

|---|---|---|

|

Foster a respectful and welcoming workplace culture Over 90% of respondents to the Engineers Canada survey in 2020 rated ‘culture change’ as an important or critical topic for building inclusion capabilities within engineering workplaces. |

|

|

| Provide work-life flexibility |

|

|

| Ensure that the work environment reflects the signs and symbols of gender inclusion |

|

|

| Rely on career and HR practices that are equitable and inclusive |

|

|

| Take purposeful actions to improve gender balance in leadership |

|

|

4. Moving forward with change

4.1 General principles relevant to gender within engineering

Beyond having particular areas of focus, a recognized challenge in achieving equity for women is the necessity of fostering an environment that is conducive to change. The following are seven general principles which may help guide individuals and organizations who want to work towards achieving gender equity in the workplace:

- Equity for women requires a multidimensional approach and long-term commitment.

Equity is not easily compartmentalized. Changes in one aspect must be reinforced with changes in another. For example, hiring talented women will have no impact on innovation if their ideas and contributions are routinely discounted in meetings. Progress on equity for women will be a continuing effort. Rather than a checklist that might soon be ‘done’, it is often described as a ‘journey’, where one step leads an organization to a new state and readiness for the next step. - Moving forward with culture change requires ‘proactive’ commitment across leadership teams, going well beyond passive endorsement.[14]

The CEO alone cannot change the culture of the entire organization – the executive team, human resources, and leaders throughout the company must play their part.[15] In some cases, leaders will not be ready to be the champions one might hope for. Some will lack interest. Some will have questions or concerns. Others might be passive in their support, unwilling to invest or persevere in the face of obstacles. Sustainable change to a more gender-inclusive workplace will be slow and difficult in this context. An intentional effort to influence them could include education about the business case, relevant success stories, one-on-one coaching, or mentoring. Involving and empowering emerging leaders who are passionate and driven to make a difference can be a helpful strategy for building leadership and change momentum.

- Effecting change in gender equity requires everyone to be part of the solution.

Discussions that lead individuals to feel ‘shamed and blamed’ are more likely to lead to resistance than to a new commitment toward change. Acknowledging that systemic barriers in workplaces have arisen through longstanding practices and attitudes that originated in times when workplaces were much less diverse can be more effective. These systems, practices and attitudes often remain unquestioned, due to unconscious bias.

- Repeated and consistent communication is critical.

Creating momentum requires ongoing and transparent communication about the current situation, the desired situation, and the gaps between the two. As was evidenced in the survey (see above), not everyone has the same understanding of today’s workplace reality. Myths and misunderstandings will stand in the way of effective progress. Expectations about the commitment and behaviour required to close the gaps must be well understood. - Measurement, monitoring, and ongoing reporting of the indicators of a gender inclusive workplace helps to focus and maintain efforts.

In the Engineers Canada survey, 1 in 8 of the male respondents indicated they “don’t know” whether gender makes a difference in someone’s workplace experience. Raising awareness of the current situation is a critical requirement for moving forward. Reporting should include insights from individuals identifying as women, as men, and non-binary or that identify as a member of an underrepresented group. - Clear accountabilities must be in place at all levels of an organization.

A desire for culture change sometimes runs the risk of becoming a situation where it is everyone’s responsibility, and therefore no one’s responsibility. Clarity about the required change and the expectations for achieving it helps everyone to see their role.- Leaders and managers at all levels should have equity-related objectives, defined competencies, and relevant skill-building, with follow-up.

- At an individual level, many organizations have outlined inclusive behaviours expected of all staff. Employers are taking action to encourage staff to be ‘allies’ who help to surface and address experiences of micro-aggression and encourage micro-affirmations and micro-interventions, instead. While sometimes these ‘allyship’ programs are designed for men[16], attention is also required to encourage individuals identifying as women or non-binary to speak up on gender equity issues.

- People who are not directly affected by the issue being faced can be powerful allies. For example, a white woman can speak up for Indigenous women, or a senior woman can advocate for parents with young children. However, often members of equity-deserving groups will not feel safe to raise issues that affect others, or themselves, for fear of direct retribution or more subtle negative impacts. Ensuring that people feel equipped and supported to be allies is critical. Similarly, it is important to ensure that individuals who feel they have been negatively affected by an issue have the confidence that their organization is a safe place to raise their concerns; in this way they can be part of supporting the wider change effort to which their leaders and organization have committed.

- Progressive learning approaches embed equity issues into ongoing work.

Learning supports can include traditional training approaches, but also job aids, team discussions, mentoring / coaching, task forces, webinars, and ongoing consistent communications (e.g., in newsletters, staff meetings, leadership messages, events). One approach that has shown success is to prompt awareness-building interactions between leaders and women engineers, such as dialogue sessions, mentoring, and reverse mentoring. These various approaches will build awareness, increase knowledge, and enhance behavioural competencies for individuals, team leaders, mentors, and senior managers.

4.2 Putting it into practice

Introducing and sustaining new behaviours is the core challenge for successful change. For successful implementation of a change in policy, programs and/or related behaviours, organizations must adopt an intentional, strategic and methodical change management approach.

A good change plan will guide efforts to actively engage leaders, sponsors and change agents throughout the organization. It will also provide an evidence-based orientation that can incorporate a variety of inputs – quantitative, qualitative, research-based and lived experience – from the full diversity of the workforce, for designing, testing, and improving solutions.

4.2.1 The ADKAR model

One approach that is widely used and well recognized is the ADKAR model[17] that considers Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability and Reinforcement. The framework rests on the idea that organizational change can only occur through individual change. For example, the most effective policies and programs for work-life balance will have no impact unless accompanied by a genuine acceptance of flexible work arrangements by colleagues and managers. In the context of addressing gender equity barriers, this implies a progressive, sequential completion of the building blocks:

4.2.2 Small wins

Another successful approach is a focus on ‘small wins’ – “a series of controllable opportunities of modest size that produce visible results”. [18] These ‘small wins’ succeed by making progressive changes in a consistent direction, attracting allies, and minimizing resistance. Years of applied research in a range of organizations has shown that a disciplined small-wins strategy for gender inclusion “benefits not just women but also men and the organization as a whole.”[19]

5. Next steps for individuals and for organizations

Canada’s engineering profession needs to attract skilled women, recognize their value, allow them to thrive, and retain them. This guideline presents strategies and approaches for understanding the current state, generating commitment and momentum, and taking and sustaining action.

There are approaches that are suitable for individual action and others that are suitable for implementation by employers. They are not mutually exclusive, but rather complementary and additive in impact.

5.1 Individuals

Engineers, managers, and leaders wishing to improve workplace equity for women cannot be bystanders. Rather, they must take accountability for individual action. While there will be differences across roles, individuals can take several concrete steps including the following:

- Building one’s own knowledge and self-awareness;

- Committing to action, such as a ‘small wins’ strategy, consistent allyship, and taking on accountability to be an agent for change;

- Leveraging one’s influence and visibility, taking individual action to foster positive and inclusive work environments – whether as colleagues, mentors, opinion leaders, managers, and organizational leaders; and,

- Showing the confidence and courage to stand up for oneself, for others, and for positions that might be challenging.

5.2 Employers

Organizations wishing to improve workplace equity for women must adopt inclusive policies and practices, implementing actions that will shape an inclusive workplace culture in the day-to-day. Employers can take a variety of actions including the following:

- Assessing not only the current state of workplace equity for women but also diagnosing the organization’s current state of diversity maturity[20] and its readiness for change;

- Gaining knowledge and expertise to identify and implement evidence-based best practices for attracting, developing, and retaining women, with diverse identity, in engineering workplaces;

- Embedding gender inclusion within core business concerns and people management practices. Re-thinking, disrupting, and re-designing the system where necessary;

- Partnering with other organizations in the broader talent system – engineering faculties, professional associations, educational institutions, and STEM agencies;

- Setting targets for gender equity and inclusion that are supported by leadership, such as 30 by 30, and the 50-30 Challenge, and/or defined improvements in employee survey results or turnover rates for women; and,

- Establishing clear standards and norms for behaviour, with learning and communication supports, clear accountabilities, and relevant rewards / consequences.

The expectation is that individuals and organizations throughout the engineering profession will take meaningful action. Commitment, accountability, measurement, and continued learning are the necessary ingredients to maintain and accelerate progress.

6. Conclusion

Engineers Canada is pleased to provide this Guideline for engineers and engineering firms on equity for women in the workplace to our country’s engineering profession. It is an important complement to the 30 by 30 initiative and is positioned to support direct action within Canada’s workplaces.

From coast to coast to coast, we believe that it is time for urgent action to create the Canadian engineering workplaces that will be equitable and inclusive for women in all their diversity. We encourage you, the reader, to turn your thoughts and behaviours toward making the change that we know is needed.

Appendix A: Additional context and rationale

Women remain significantly under-represented in engineering.

In 2020, 14.2 per cent of the members of the engineering profession in Canada were female-identifying (an increase from 13.9 per cent in 2019).[21] Year-over-year progress toward more equitable participation is generally regarded as disappointingly slow.

Figure 4: National statistics of the sex distribution among newly licensed engineers (binary only)

The 30 by 30 initiative has set an objective of having women represent 30% of newly licensed engineers by the year 2030. The most recent data show that just over one-fifth (20.6%) of newly licensed engineers in 2020 identified as women. This is an encouraging increase from the 2019 level of 17.9%, which had moved only marginally from the 2014 level of 17.0%.[22] Future data collection will assess whether this most recent increase is being sustained.

A focus on the postsecondary ‘pipeline’ is necessary but not sufficient.

There are many programs under way to encourage young women to develop and sustain interest in STEM fields.[23] Within accredited postsecondary engineering programs, Engineers Canada statistics reveal that females represented 23.4% of undergraduate enrolment in 2019. This reflects a steady increase in the last 10 years, growing from 17.7% in 2010. For the 2019-2020 academic year, Statistics Canada reports that only 21.8% of students in Canadian engineering and engineering technology programs were female-identifying.[24] This proportion of just over ‘one in five’ was the lowest among the ten fields of study reported. The proportion of female-identifying was slightly higher among international students (24%).

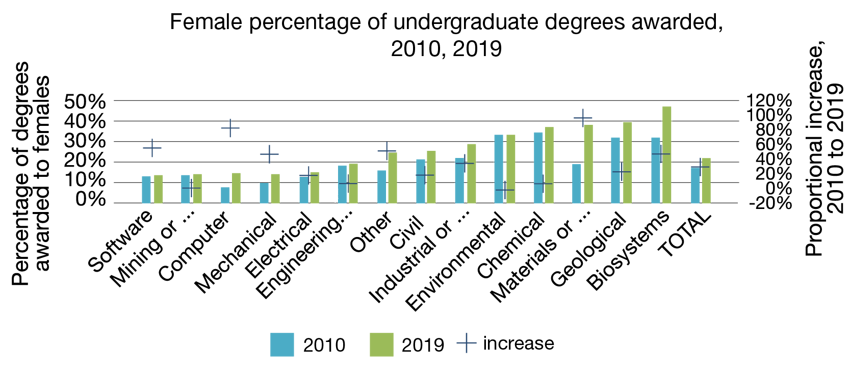

The representation of female-identifying students varies significantly across disciplines within engineering. Software, mining, computer, mechanical and electrical engineering consistently see the lowest levels of female representation in degrees awarded, while biosystems, geological, chemical and environmental see the highest levels (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Engineering undergraduate degrees awarded to females, by discipline, with percentage increase (2010, 2019)[25]

An equitable workplace is expected – it is the ‘right’ thing to do.

Employers are increasingly expected to demonstrate commitment and tangible progress toward having a workplace that reflects the diversity of the communities in which they work, and which is characterized by inclusive approaches and perspectives. News items, social media, shareholder meetings, government investments, and stakeholder commentaries are public reflections of the ongoing shift in societal expectations. There is a clear growth in the expectations for improving the representation levels of women, more specifically. These expectations are set out in professions[26]; in governance frameworks[27]; in industry accords and commitments[28]; in vendor criteria laid out in contracting opportunities[29]; and elsewhere.

Within the engineering profession, the characteristics of an inclusive, equitable and welcoming workplace already align directly with the key points of the profession’s ethical standards. These statements capture well the profession’s expectations not only of individual engineers, but also of those work environments that they work within and influence. The Engineers Canada Code of Ethics[30] describes conduct that would also foster an equitable environment for women:

- Very generally, registrants are expected to “Uphold and enhance the honour and dignity of the profession”.

- More specifically, registrants are expected to “Conduct themselves with integrity, equity, fairness, courtesy and good faith towards clients, colleagues and others”, “Promote health and safety within the workplace”, and “Treat equitably and promote the equitable and dignified treatment of people in accordance with human rights legislation”.

An equitable workplace makes good sense – it is the ‘bright’ thing to do.

It will take concerted action from a range of stakeholders to create truly equitable and inclusive workplaces for women in engineering. Fortunately, these stakeholders also benefit directly from the changes that lead to greater equity for women.

In a competitive labour market, employers with a track record of success with gender equity will have the advantage in attracting talent. In a large-scale study of millennials, PwC reported that 82% of females and 74% of males identified an employers’ set of policies on diversity, equality, and workforce inclusion as an important factor when deciding whether or not to work for an organization[31].

Accessing skilled engineering talent has perhaps never been as critical a concern as it is now. Infrastructure investments and a range of innovation challenges are undeniably high on the national agenda. When engineering jobs cannot be filled, projects may be understaffed or short of key qualifications, thereby creating risks to project success. Hiring a wide range of talented engineers helps avoid negative trickle-down impacts on our success with climate change commitments, manufacturing, resource extraction, power generation, construction, public service, health, and others. The profession cannot afford to lose talented women to other, more inclusive professions and industries.

Equity for women in a workplace helps organizations achieve better business outcomes. A considerable body of research evidence confirms that increasing gender diversity is linked to improved results in important indicators such as innovation, financial results, risk mitigation, safety, and employee engagement.[32]

The changes required to achieve equity for women will benefit all workers by providing more equitable career opportunities, more supportive policies, and a more satisfying and engaging workplace experience. Beyond gender, a broader focus on diversity and equity overall will lead to important benefits related to inclusion across race, ethnicity, (dis)ability, age, sexual orientation, and other identities.

Finally, there are important benefits to be achieved at a societal level. While professional practice and sound methodologies are foundational, an engineering profession that also has more diverse perspectives and ‘lived experience’ will better reflect society and have an advantage in understanding its needs.

Appendix B: Glossary

30 by 30: The ‘30 by 30’ initiative, first conceived by the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of Alberta (APEGA) in 2010, was adopted by Engineers Canada as the national goal of raising the percentage of newly licensed engineers who are women to 30 per cent by the year 2030.

50-30 Challenge: The Government of Canada’s ‘50-30 Challenge’, led by Innovation Science and Economic Development (ISED), aims to promote voluntary action toward diversity on boards and/or in senior management. It asks large employers, small-medium enterprises, and other organizations (post-secondary, non-profits, etc.) to aspire to two goals: gender parity (“50%” women and/or non-binary people) and significant representation (“30%” other equity-deserving groups) on Canadian boards and/or in senior management.

Ally: An ally takes supportive action to address barriers, harassment, micro-aggressions or other workplace dynamics that are likely to disadvantage members of equity-deserving groups (other than their own). Allyship goes beyond “see something, say something”; in its best form, it includes taking self-aware, informed, strategic actions for systemic change.

Diversity: Captures the psychological, physical, and social differences that occur among any and all individuals. People differ by attributes such as age, race, education, mental or physical ability, learning styles, gender, sex, sexual orientation, immigration status, religion, socioeconomic status, family status, and others. A diverse group, community, or organization is one in which a variety of social and cultural characteristics exist.

Female, female-identifying, women: The guideline uses the gender identity term ‘women’. Where it is more appropriate to refer to the gender diversity of lived experience, to categorize sex, or when sharing results of a binary sex survey, ‘female-identifying’, or similarly ‘identifying as female’ is used.

Gender: Socially constructed ideas and characteristics of women, men and non-binary individuals – such as norms, roles, behaviours, and relationships of and between groups. Terms such as genderqueer, gender-nonconforming and others are used to reflect some of the diversity of gender identities in the population.

Gender equality: Equal chances or opportunities for groups of women, men and non-binary individuals to access and control social, economic and political resources, including protection under the law (such as health services, education and voting rights). It is also known as equality of opportunity – or formal equality.

Gender equity: More than formal equality of opportunity, gender equity refers to the different needs, preferences and situations of women, men and non-binary individuals. This may mean that different treatment is needed to ensure equality of opportunity. This is often referred to as substantive equality (or equality of results) and requires considering the realities of the lives of women, men and non-binary individuals[33].

Inclusion: Environment in which all people are respected equitably and have access to the same opportunities. Requires the identification and removal of barriers (e.g., physical, procedural, visible, invisible, intentional, unintentional) that inhibit participation and contribution.

Intersectionality: Adopting an intersectional perspective recognizes that people have multiple and diverse identity factors (beyond gender) that intersect to shape their perspectives, ideologies and experiences. This perspective can provide a more comprehensive view of systemic impacts that are interconnected and cannot be examined separately from one another (e.g., racism, sexism, homophobia, etc.).

Micro-aggression: Workplace microaggressions are subtle behaviors that affect members of marginalized groups such as women but can add up and create even greater impacts over time. Examples include ignoring or discounting the person’s input in a meeting, making assumptions about the person’s place of origin, and making a comment (even a positive one) that reflects stereotypes.

Non-binary: Non-binary individuals do not identify exclusively as a man or woman. They may identify as being both a man and a woman, somewhere in between, or as falling completely outside these categories. The term non-binary can be specific or an umbrella term. Examples of non-binary identities can include (but are not limited to) genderqueer, genderfluid, two-spirit, and agender.

Sex: Classification of individuals based on biological and physiological differences of males, females and intersexed individuals. Sex is distinct from gender, which is based on social constructions such as roles, norms, and patterns of behaviour.

Unconscious bias: Everyone has unconscious assumptions, beliefs, attitudes and stereotypes that their brains have developed about different groups. They can be positive, negative, or neutral. These learned mental short-cuts affect how we perceive and respond to people, preventing us from clearly seeing fairly and accurately the information or the person in front of us. Unconscious biases can be triggered within a fraction of a second, affecting decision-making in ways of which we are generally unaware.

Appendix C: Change Agent Tools and Examples

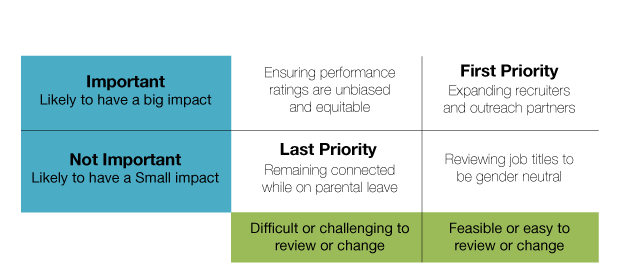

Tool: Choosing a policy, process or procedure as the focus or starting point

Organizations or change agents can sometimes be overwhelmed by the number of opportunities for change. A straightforward comparison of effort vs. potential benefit can help to get started.

Review any assessment findings that depicted the “as-is” workplace – where are the recognized ‘pain points’ or the barriers to women’s participation?

Make a list of possible policies, processes or procedures that might be worth reviewing. For each one, estimate how much impact a change might have. Then, estimate how difficult it might be to change that policy, process or procedure.

Based on the ratings, place the policies, processes and procedures in the appropriate box of a simple matrix.

Look at the results to prioritize them and to choose a starting point. The diagram below shows a few hypothetical examples to demonstrate this matrix might be used.

Often, some important and unintentional systemic barriers are found in policies, processes or procedures such as:

- Recruitment and hiring processes and procedures

- Promotion and transfer processes

- Job titles and job evaluation processes

- Policies about working hours and flexibility or personal time off

- Procedures that are seniority-based, such as requesting vacation or work shifts

Tool: Gender Analysis Key Questions

Are there any unintended gender barriers that can be removed by updating the policy, process or procedure?

- What is the written policy, process or procedure?

- Obtain a copy.

- Find out who has the responsibility or ownership for it.

- What is its purpose and where does it apply?

- Summarize the intended benefit of the policy, process or procedure. Any proposed changes should be aligned to this purpose.

- Make a list of the people or groups who are affected by the policy, process or procedure.

- How might it affect women and men differently?

- Ask the group that ‘owns’ the policy, process or procedure about any gender implications that they are aware of or have considered.

- Interview a few women and men about their experiences with this policy, process or procedure. Questions to ask might include:

- What impact has this policy, process or procedure had on you?

- In your experience, how is this policy, process or procedure applied, compared to the way it is written?

- What changes to this policy, process or procedure might make it better for you?

- Find any other information that might help to understand the impact of this policy, process or procedure on women and on men. Some ways that women and men and people with non-binary gender identities might be affected differently include:

- Financial impacts

- Health and wellness

- Safety and personal risk

- Ability to manage work/life balance

- Job satisfaction

- Career opportunities

- Access to training

- Common sources of information would be: Accounting or Human Resources staff, administration at a field site or in the local office, Health & Safety departments, and local managers. Ask them to provide information separately for men and women, if possible.

- What conclusions can be drawn about whether there are any gender barriers in this written policy, process or procedure?

- Analyze the information collected, to identify any gender-related systemic barriers.

- Validate the conclusions with a group of knowledgeable people in the company.

- What changes would be helpful?

- Get good ideas by reading some resource material, talking to some women and men, or talking to the group that ‘owns’ the policy, process or procedure.

- List one or more changes to the policy, process or procedure that would eliminate the systemic barrier(s).

- Evaluate the proposed changes and make a decision or recommendation.

Putting it into practice: Case studies* for making systemic change

| Concern or ‘Pain Point’ | Assessment | Taking Action |

|---|---|---|

| Our organization seems to attract few women applicants |

|

|

| Mid-career women engineers have complained about lower earnings |

|

|

| We have few women ready to advance into leadership positions |

|

|

*Hypothetical, but representative, examples

Appendix D: Sample Resources

This curated list is intended to provide sources for appropriate tools, credible engineering-relevant information sources, and guidance for further exploration as a starting point.

Specifically, the resources provide one or more of the following:

- Background and context;

- Research summaries specific to women in engineering and STEM fields;

- External trends and current initiatives; and,

- Relevant strategies and best practices for increasing the percentages of women in engineering occupations

1. Engineers Canada: 30 by 30 and beyond: Environmental Scan Report

https://engineerscanada.ca/sites/default/files/diversity/30-by-30-and-beyond.pdf

This 50-page report from Engineers Canada provides:

- An overview of the 30 by 30 work done to date

- Recent statistics on women’s participation in engineering, at various points in the continuum (early education, post-secondary education, engineering profession)

- Barriers to women in engineering (in recruitment, retention, professional development)

- Examples of external trends and comparators

- The role of Engineers Canada

- Analysis and recommendations

For a quick read:

- See the leaky pipeline figure (p. 24). It demonstrates that engineering loses women at the entry to postsecondary, and at the transition from postsecondary to licensed engineers.

- Read Sections 3 to 6 (pp. 32 to 50), starting with Barriers and ending with Recommendations

2. Research reports and employer guides: Engineering associations and regulators across the country have conducted comprehensive research programs and developed pragmatic guides for employers. Three examples are listed here.

OSPE Report: Calling all STEM Employers: Why workplace cultures must shift to change the gender landscape

https://ospe.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/breaking_barriers_white_paper_report_single.compressed.pdf

This 18-page report from the Ontario Society of Professional Engineers provides:

- Results from interviews, focus groups and surveys (Ontario and nation-wide)

- Comparisons of career barriers reported by men and women working in STEM fields

- Recommended actions for employers and for educational institutions

This report is a quick read. For particularly compelling summaries,

- See the graph on p. 7 that ranks the workplace challenges to advancement, separately for men and women. It shows that ‘Feeling disrespected and undervalued’ and ‘Lack of mentorship opportunities and/or role models’ are reported as barriers by more than 40% of the 1700+ women who responded to the survey.

- See the Key Findings summarized on p. 13.

- Review the recommendations for employers on p. 16

APEGA: Women in the Workplace: A Shift in Industry Work Culture

https://www.apega.ca/docs/default-source/pdfs/wage-2021-abridged-report.pdf

This report from the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of Alberta (APEGA) provides the results of a three-year project to examine the barriers faced by women in engineering and geoscience workplaces. The initiative included an online survey, consultations, a pay equity analysis of five years of provincial survey data, labour market data within the profession, and a pilot project with five employer partners.

For a quick read, there are several infographics and short action tips. Two summary pages (pp. 34-35) provide 7 to 10 suggested actions for individuals, for leaders, and for organizations.

The project also produced a guidelines document. The project overview can be found at: https://www.apega.ca/members/equity-diversity-inclusion/wage-grant-project

OIQ: Femmes en génie: Guide de l’employeur pour un milieu de travail plus diversifié, inclusif et équitable

https://www.oiq.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/documents/Communications/femmes_en_genie_guide_employeur.pdf

This employer guide from the Ordre des ingénieurs du Québec (OIQ) complements the Order’s previous efforts to attract and support girls and young women in choosing a career in engineering. It begins with a few infographics addressing the representation rates for women in the profession. Short, reader-friendly sections present key points of the business case for greater diversity and some of the critical barriers and challenges for women in engineering.

The second half of the report focuses on action recommendations for employers, including:

- Doing a workplace assessment;

- Setting targets; and,

- Creating an action plan for recruitment, performance management and retention, and professional development.

Short “did you know” call-outs provide an evidence base for the recommendations.

Four brief case studies of small and large engineering work environments give examples of successful approaches.

3. Series of four infographics from “Engendering Success in STEM” and related research networks: selected findings from research projects involving a network of Canadian universities.

https://successinstem.ca/resources/

These resources include a series of infographics that are each 1-3 pages long, plus short reference lists. They have been selected to address the following issues:

- Understanding workplace diversity – for managers. See this for a foundational view of the business case and key issues in diversity issues related to gender.

- Bias busting strategies – for institutions. This one-page infographic lists six evidence-based strategies and actions for STEM workplaces to counteract implicit bias.

- Gender inclusive policies and practices in engineering. This describes how inclusive policies create positive social climates, thereby reducing the ‘social identity threat’ that affects women’s decisions to stay in STEM fields.

- Intersectionality in STEM – These research findings highlight that women’s various identities will affect their experience.

4. DiscoverE report: Despite the Odds: Young women who persist in engineering (Executive Summary)

https://discovere.org/resources/despite-the-odds-young-women-who-persist-in-engineering/

This 16-page summary of a literature review identifies the personal factors that are linked to whether young women choose engineering and/or whether they persist in engineering studies. The report is an easy read, well-structured to highlight the relevance of 7 factors such as young women’s interest and attitudes toward engineering; their own sense of self-efficacy; and their sense of belonging. In reviewing the findings, consider the possible implications for engineers and engineering firms.

5. Symposium report from May 2019: Women and the workplace – How employers can advance equality and diversity

https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/reports/women-symposium.html

This 52-page report summarizes presentations and discussions from a two-day event with 240 Canadian leaders and champions from a wide range of sectors and organizations. It captures many recent research findings and gender equality initiatives and trends in a user-friendly format. The last section (pp. 35 to 52) provides an annotated listing of organizations and resources for promoting workplace gender equality.

For a quick read:

- The Executive Summary highlights three components for focus:

- Increasing awareness and challenging widespread myths;

- Changing structures instead of people; and,

- Adopting an intersectional approach.

- The Executive Summary also lists several best practice strategies for hiring, employee retention and career advancement.

- Throughout the document, brief descriptions of particular issues and solutions are good snapshots.

6. “Assembling the Pieces - An Implementation Guide to the National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace”, Standards Council of Canada, 2014

https://www.csagroup.org/documents/codes-and-standards/publications/SPE-Z1003-Guidebook.pdf

This guide to support an organization’s implementation of the CSA National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace is lengthy (160+ pages) but user-friendly. It offers practical steps and guidance for taking action to build a workplace environment that is welcoming, inclusive and psychologically healthy. While not specifically focused on issues of equity for women in engineering, it nonetheless offers a comprehensive set of relevant checklists, tools and techniques.

7. “Women in Consulting Engineering in New Brunswick: Career Satisfaction & Workplace Experiences”, Association of Consulting Engineering Companies – New Brunswick, 2020.

https://www.acec-nb.ca/uploads/1/3/6/3/136372220/acec_nb_final_march_27.2.pdf

This research report explores attractors to women in consulting engineering, including meaningful types of benefits, drivers of career satisfaction, perceptions of career advancement opportunities, and work culture. Quantitative and qualitative data from a survey, focus groups and telephone interviews are presented under key themes. Recommendations for employers as well as for an industry association translate the findings into pragmatic courses of action. The topics, consultation questions and the recommended practices are relevant to small, medium and large organizations that want to undertake efforts toward greater equity for women in their workplaces.

8. DiversifySTEM online materials developed by the Ontario Society of Professional Engineers (OSPE)

https://diversifystem.ca/all-lessons/

This suite of easy-to-use quick learning supports walks the user through a process of identifying key aspects of gender diversity, assessing their organization, and deciding on courses of action. It is easily customized to the user’s particular interests and knowledge level. It can be started, set aside, and completed at another time. The resources are visually appealing and concise.

9. Society for Women Engineers materials for learning methods and discussion sessions

https://swe.org

This U.S.-based organization offers a range of learning supports focused on increasing workplace inclusion for women in engineering. The materials range from learning cards applicable in global workplaces, to facilitator guides for group sessions, to webcasts exploring lived experience. These materials have a strong intersectional lens and can be useful new approaches for engaging leaders and employees in the topics of equity.

10. Research perspectives on women, work and the COVID pandemic

These resources capture recent information available on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on working women. They document the related opportunities and potential risks to women’s advancement into fields such as STEM, in the context of the pandemic.

- Statistics Canada report: Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, April 2020 to June 2021 Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210804/dq210804b-eng.htm

- Engineers Canada: November 2020 Submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women on the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women. Available at: https://engineerscanada.ca/sites/default/files/public-policy/public-policy-document/fewo-impact-of-covid-19-pandemic-on-women.pdf

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on gender-related work from home in STEM fields—Report of the WiMPBME Task Group. This survey suggests that the burden of childcare and household duties will have a negative impact on the careers of women if the burden is not more similar for both sexes. The authors emphasize that a change in policies of organizations may be required to minimize the negative impact on the professional status and career of men and women who work in STEM fields. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gwao.12690

- The Association of Consulting Engineering Companies in BC (ACEC-BC) has produced resources to support organizations in their efforts to consider and make progress on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Practical advice for remote teams and culture change toward EDI in the ‘new normal’ is available on their website: https://acec-bc.ca/resources/

Additional resources:

- Engineers Canada: guide that the 30 by 30 network has compiled with various tactics that can increase diversity and women’s participation at various levels of an organization.

- Engineers Canada: one-hour training webinar for engineering and geoscience professionals of all levels that will introduce them to the topics of equity, diversity, and inclusion in the workplace.

- Engineers and Geoscientists British Columbia: Professional Practice Guidelines – Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. The document was created to guide professional practice related to equitable, diverse, and inclusive environments and interactions. The guidelines provide a high-level description of EDI concepts and challenges that may arise, and outline specific expectations and obligations for individual and firm registrants of Engineers and Geoscientists BC.

Endnotes

[*] In 2020, Engineers Canada conducted a survey on women in engineering workplaces and current engineering workplace practices. This survey will be referred to as Engineers Canada 2020 Survey throughout the guideline.

[†] “Non-binary” is used as an umbrella term throughout the guideline.

[‡] Hypothetical, but representative, examples

[1] Sex and gender definition: Sex identifiers have historically been limited to ‘male’ and ‘female’ in the survey of national membership. For the purposes of this survey, data on sex was recorded with three options: “Male”, “Female”, or “Gender Unknown”. We use “female-identifying” to describe participants who selected female, and “male-identifying” to describe participants who selected male, to acknowledge the gender diversity that exists within these sex identities. “Gender Unknown” indicates that the members did not provide a sex identifier.

[2] “Engineers Canada Strategic Plan 2019-2021," Engineers Canada, November 8, 2019.

[3] Research references are provided in the document and in the curated list of resources.

[4] DiversifySTEM website, Ontario Society of Professional Engineers. Accessed November 2021.

[5] See, for example, “The EGBC Code of Ethics”, Engineers & Geoscientists of BC, March 12 2021.

[6] For example:

- Labour force statistical data can be explored at a level of analysis that will reflect an organization’s context and identify specific gaps in women’s representation.

- The Global Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Benchmarks (GDEIB) can be used to assess an organization’s practices.

- The federal government’s GBA Plus (Gender-Based Analysis Plus) lens provides a thorough analytical approach.

[7] See the Glossary.

[8] See Global Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Benchmarks: Standards for Organizations Around the World (2021) for the full set of benchmarks and other supporting tools.

[9] https://women-gender-equality.canada.ca/en/gender-based-analysis-plus.html

[10] See Perez, C. C. (2021). Invisible Women: Data bias in a world designed for men. Abrams Press.

[11] Morissette, René. “Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, April 2020 to June 2021”, Statistics Canada - Social Analysis and Modelling Division, August 4, 2021

[12] It is useful to note that these responses are from men who chose to participate in a survey about gender equity. We cannot be certain how representative they are of the wider population of men – it is possible that the perspectives of men who did not participate might be different, perhaps showing even less awareness of the challenges faced by women. Regardless, the available data are sufficiently clear to warrant reflection.

[13] See:

- “Psychological health and safety in the workplace - Prevention, promotion, and guidance to staged implementation”, CAN/CSA-Z1003-13/BNQ 9700-803/2013; Standards Council of Canada, January 2013 and Reaffirmed in 2018.

- Collins, J. “Assembling the Pieces - An Implementation Guide to the National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace”, Standards Council of Canada, 2014.

[14] Orser, B. (2001). Chief Executive Commitment: The Key to Enhancing Women’s Advancement. Conference Board of Canada.

[15] Barsh, J., Nudelman, S., & Yee, L. (2013, April). “Lessons from the Leading Edge of Gender Diversity”. McKinsey Quarterly.

[16] See, for example, N.L. Wilson, T. Dance, W. Pei, R.S. Sanders, A. Ulrich (2021). “Learning, experiences, and actions towards advancing gender equity in engineering as aspiring men’s allyship group”. Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 99:2124-2137

[17] The Prosci ADKAR Model, Prosci, 2021

[18] Weick, K. E. (1984). “Small wins: Redefining the scale of social problems”. American Psychologist, Vol 39(1), 40-49.

[19] Meyerson, D., & Fletcher, J. K. (2000). “A modest manifesto for shattering the glass ceiling.” Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 126-36.

[20] ‘Diversity maturity’ is a term that generally reflects an organization’s progress to date on a number of dimensions related to diversity, equity and inclusion.

[21] 2021 National Membership Information” Engineers Canada, November 2020 -- Due to low numbers, the counts for those identifying as neither female nor male have been excluded here

[22] “2021 National Membership Information” Engineers Canada, November 2020 -- Due to low numbers, the counts for those identifying as neither female nor male have been excluded here.

[23] Programs available in various locations across the country can be readily found through online and other published sources.

[24] Statistics Canada. Table 37-10-0163-02 Proportion of male and female postsecondary enrolments, by International Standard Classification of Education, institution type, Classification of Instructional Programs, STEM and BHASE groupings, status of student in Canada and age group. The 21.8% figure includes both Canadian and international students.

[25] Figures for the chart have been extracted from:

- “Trends in Engineering Enrolment and Degrees Awarded 2015-2019”, Engineers Canada, 2020

- “Enrollment up in accredited engineering programs: 2010-2014 Enrolment and Degrees Awarded Report”, Engineers Canada, November 18, 2015

[26] Including examples such as law, accounting, and medicine.

[27] Such as ISO 26000; UN Sustainable Development Goals; Canadian corporation reporting standards on diversity; Employment Equity and human rights frameworks.

[28] Including examples such as the electricity sector’s “Leadership Accord for Gender Diversity”, Electricity Human Resources Canada (EHRC), 2017; or the “50-30 Challenge” from Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada.

[29] Including examples such as Requests for Proposals and Supplier Codes of Conduct.

[30] “Public Guideline on the code of ethics”, Engineers Canada, March, 2016

[31] Flood, Aoife. “Next Generation Diversity: Developing tomorrow’s female leaders”, PWC, 2016.

[32] See for example:

- Business case: WWEST has published an infographic and research scan summarizing some of the business benefits of gender diversity. Westcoast Women in Engineering, Science and Technology (WWEST), (2014), The Business Case for Gender Diversity. https://wwest.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2014/05/Business-Case-for-Gender-Diversity.pdf

- Financial: McKinsey research shows that companies in the top quartile for gender diversity are 15% more likely to have financial returns above the median of their respective national industry medians. McKinsey and Company, January 2015, Why Diversity Matters. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/why-diversity-matters

- Employee engagement: McKinsey Canada reports research showing that 90 percent of employees are more likely to go out of their way to help a colleague if they work in an inclusive organization and are 47 percent more likely to stay with an organization if they consider it to be inclusive.

McKinsey and Company, November 2021, Gender Diversity at Work in Canada. https://www.mckinsey.com/ca/~/media/mckinsey/locations/north%20america/canada/gender%20diversity%20at%20work/gender_diversity_at_work_in_canada.pdf - Innovation. S.A. Hewlett, M. Marshall, L. Sherbin. (December 2013). “How diversity can drive innovation”. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2013/12/how-diversity-can-drive-innovation

[33] Video from Status of Women Canada that explains the difference between equality and equity:

https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/med/multimedia/videos/gba-acs-ee-en.html

[34] Taylor, J. “Engineers Canada’s submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women on the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women”, Engineers Canada, November 2020.