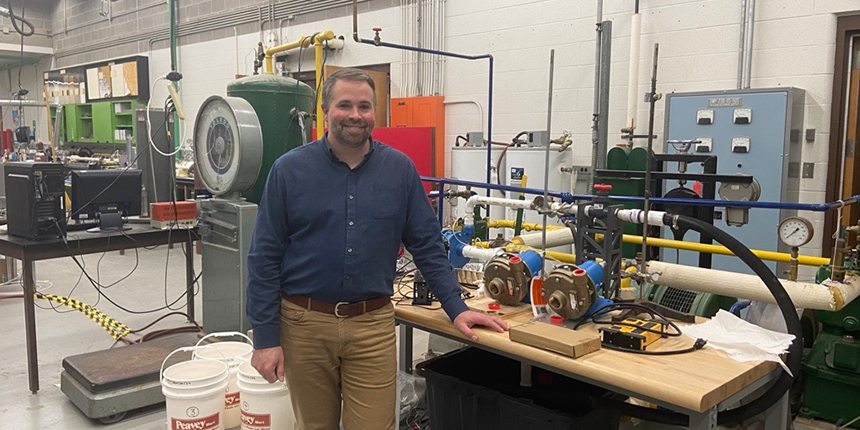

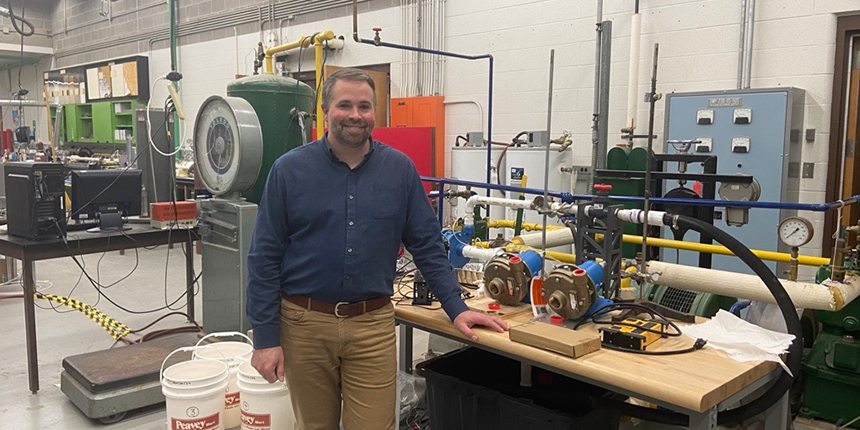

Philip LePoudre, P.Eng., a mechanical engineer with a specialization in HVAC systems, used creativity and perseverance to create an innovation that has changed cooling systems around the world, including the data centres that power Meta.

In a story that begins with foundational research and manufacturing design, journeys through years of Canadian investment and innovation, faces challenges and setbacks, and ultimately leads to international commercialization, Philip LePoudre, P.Eng., tells the tale of Canadian engineering.

LePoudre, a mechanical engineer with a specialization in HVAC systems, has grown up living and working in Saskatoon. His work on a membrane exchanger technology, originally meant for energy recovery, changed the way evaporative cooling systems were applied across the world. His success is a testament to the perseverance and support of the Canadian engineering profession.

Setting the foundations

While LePoudre always knew he was going to become an engineer, working with HVAC systems was not the direction he expected. When he decided upon his Masters, however, LePoudre was drawn to computational fluid dynamics, which involves computer simulations of fluid flow, including air and liquid flows. That might sound abstract, but systems regulating air and water are integral to our buildings, ensuring that they are well ventilated as well as heated or cooled during various seasons.

While working at the University of Saskatchewan, his alma mater, LePoudre became involved in the HVAC research that the university was conducting. The foundational research was for a completely new type of membrane exchanger technology. “It was quite revolutionary technology,” LePoudre said. So revolutionary that it was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) funding for years, and in that time the university had developed solid foundations of this research and were ready to take it to the next level—commercialization. This is where LePoudre came in, but he didn’t come alone.

LePoudre began working with a small company called Venmar CES. Venmar specialized in manufacturing ventilation, energy recovery, and heat recovery for commercial buildings. They heavily invested in research and development and were the industrial sponsor for this early research. Once LePoudre joined, they began growing their R&D team in preparation for commercialization of the technology.

Industry and innovation

“Energy efficiency of a building is really critical,” LePoudre explained. When supplying fresh air through ventilation it has to be changed to make it suitable for the space, using energy to heat or cool the air and control humidity as needed. The best way to conserve energy therefore is to recapture heat, and ideally moisture, from air that is on its way out and use it to pretreat the air coming in. This is where the membrane technology comes in.

“The liquid-air membrane exchanger initially was developed for energy recovery, and it uses a liquid desiccant fluid that can absorb both heat and moisture and transfer it from one airstream to another,” LePoudre explained. By ‘liquid desiccant’ LePoudre is referring to a salty, corrosive fluid used in the system. The trick is to keep the corrosive liquid sealed away from the air—something no other exchanger could do until this new technology was developed.

“Think of a GORE-TEX jacket,” LePoudre said. “The material seals so that liquid can’t pass through but it's breathable to vapour, so it allows the exchange of heat and moisture vapour between air and that liquid.”

The concept was exciting and completely revolutionary. To make it commercial, however, required a lot of work. Joining Venmar’s R&D team, LePoudre and a crew of engineers got to work. “We had to do everything from scratch, so we had to develop designs, and prove that we could meet cost targets. We had to figure out how to manufacture it and develop the reliability,” LePoudre said. Without Venmar’s investment, along with the NSERC support, it would not have been possible.

“I think the most satisfying part was the first viable design. When we had all the basic elements of the design figured out the performance was significantly improved, and it was more compact than any past design and it was robust and strong. That was the most satisfying part, having something that can work in the real world. It's not just an idea,” Le Poudre reminisced.

Twists in the road

If you think that’s where this story ends, you would be incorrect. Industry is constantly changing and moving. As LePoudre said, “If you read the history of technology, it's never very easy to do something that's really game changing.” In this case, the final product never made it out of Venmar. It had some issues in field testing and the company felt it was no longer a cost-effective product.

Innovation, however, is never wasted. LePoudre thought about the potential applications of the membrane technology and came to the idea of using it for evaporative cooling. “Instead of using that salt solution, we could use water inside of those membrane channels. And as water evaporates through the membrane it produces cooling,” he explained. “I just could see the advantages of evaporative cooling application and it would be simpler to commercialize, less risky. The advantages and the performance would be quite significant.”

In 2015, LePoudre and Venmar got their lucky break by flying out to pitch this technology to Facebook (now Meta) as a potential cooling system for their data centres. By proving that the key features of this technology would be a massive increase in energy and water efficiency— in some cases saving up to 90% of the water of a more conventional evaporative cooling system—Facebook came on board.

This time the newly dubbed StatePoint technology became fully commercialized, eventually being sold and installed in Ireland, Singapore, and across Asia.

Engineering in Canada

Currently, LePoudre has embarked on a new adventure, starting his own engineering consulting company, Vital Designs Solutions. He is, of course, still proud of StatePoint Technology and all the work that led to its development.

“This story goes far beyond me. It's a story of how we can create world class technologies here in Canada, even in Saskatchewan, in Saskatoon. With the talented engineering staff, we have the people, we have the programs, we have the universities, we have the research and development funding—we have it all here in Canada,” LePoudre said. He now wants to take everything he’s learned and use it to help drive new innovation and creativity in Canadian engineering.

For LePoudre, there is an unlimited supply of problems to solve and challenges to tackle through engineering. “If you really care about a problem, and care about a customer and what they need to do, you can really achieve a lot as an engineer. You can come up with new solutions and new ideas that really change things for the better,” he said, “and I want to share that enthusiasm and that mission with others.”

New engineers are facing more complex problems, as many solutions need to balance multiple needs. In order to engineer for the future, the work has to take into account energy efficiency, reduce carbon emissions, and be accessible to everyone. These are challenges up and coming engineers should embrace. “It requires deeper levels of thinking, to address some of these issues and it takes even deeper levels of creativity and innovation and courage.”

The challenge of engineering, of course, is matched by the reward of taking part in meaningful work, in a field that will match complex challenges with a lifelong career of creativity, passion, and innovation.

Engineers build more than just bridges. Building Tomorrows is a series that highlights the important contributions of engineers and the many ways they help to make our world a better place.