Jean-Paul Pinard has a plan to help the Yukon and the North wean itself off fossil fuels through renewable wind energy.

Jean-Paul Pinard speaks from a small green office room. Behind him are shelves stacked with papers and books; on the wall are beautiful images of wind turbines. Clearly and confidently, Pinard lays out exactly how he plans to save his small corner of the world and wean the Yukon off fossil fuels and onto renewable wind energy. He’s hoping that with proof of concept, the rest of the North will follow suit.

Pinard knows the value of persistence. He has lived in the Yukon for over 30 years and spent most of his career as a mechanical engineer focused on the pursuit of a singular goal: bringing renewable wind energy to the North.

Finding inspiration

Pinard confesses to being rather mechanical in his thinking and decision-making. His older brother entered engineering before him, providing a close source of inspiration.

“He's seven years older than me, so I had time to think about it while he went to school,” Pinard admits.

Pinard wanted a field of engineering that would provide versatility and made his way into mechanical engineering. While working in the Yukon, most of the jobs he took involved working for surveying companies. When this became repetitive, he decided he needed to try something new. He found unexpected inspiration from his future wife and business partner, Sally Wright.

In 1994, Wright was living off the grid, complete with solar panels and storage batteries. It was through working on her system that Pinard decided what his next steps would be. “I decided I wanted to pursue renewable energy,” he says, “I wanted to help... save our planet.”

This decision would put him in touch with the man who became his mentor, Doug Craig. Craig was working at Boreal Alternate Energy Centre, at the time a local nonprofit organization in Whitehorse. He was the one who first introduced Pinard to the possibilities of wind. This would lead Pinard to hone his specialty, complete a Ph.D. on modelling wind in the mountainous terrain of the Yukon, and shape his career going forward.

“To become an engineer,” Pinard says, “[You have to] be curious. Don’t be shy. It’s okay to ask a lot of questions.” Pinard is a man who takes his own good advice—he immediately began investigating wind power feasibility in the Yukon, connecting with utility companies to discover what different communities needed.

Untapped potential

“There's generally three main energy needs in the community,” Pinard explains. In the North, people need electricity for lights and appliances, fuel for transportation, and energy for space heating. That last sector, space heating, consumes the majority of a community’s energy.

Pinard uses the example of a nearby town, Burwash Landing, where roughly 60 per cent of their energy goes to space heating in some form. But this energy is rarely included in assessments of energy use. For instance, a utility company might say that 93 per cent of electricity is from hydro and 7 per cent from diesel fuel. These numbers, however, don’t include energy used for transportation or space heating. With these included, hydro use shrinks to providing only a third of the community’s overall energy needs. Across the North, renewable energy represents less than one per cent of energy consumed.

Pinard would like to see that number increase dramatically and has targeted space heating. In the winter, the amount of energy used for space heating rises dramatically; it is also the time of year when the wind is at its strongest.

“Wind is a huge untapped renewable resource that we have here in the North... there's a lot of people who just haven't quite grasped it," Pinard explains. The strong winds are more than enough to meet demand, provided the correct infrastructure for storage is put into place. In a serendipitous stroke of luck, the North’s largest source of energy consumption provides the best solution for this problem.

Electrical thermal storage (ETS), Pinard explains, “basically replaces an oil furnace.” During the exceptionally windy winter days, the excess energy generated is stored in the ETS in the form of heat. When the wind dies down, the stored energy is available to keep heating the house.

Laying the groundwork

It sounds very simple. Wind energy, stored in the form of heat, can be used to heat homes during the winter. But this solution requires a lot of planning and research to be conceived and implemented.

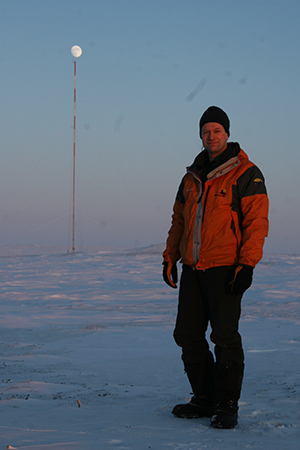

“I'm a scout... I do the initial assessment and then recommend to those in charge what to do next." To accomplish this scouting, Pinard builds and installs meteorological towers.

These towers can be anywhere from 10 to 60 meters tall. They measure values such as wind speed and direction, temperature, barometric pressure, and humidity. The data collected from the tower is used to determine the potential for wind energy in that area.

Wind power alone is not the deciding factor. A community’s infrastructure and power grid must also be assessed. Back in 2016, Pinard addressed this issue through collaboration with Yukon University and the four electric power utilities in the North to create the Northern Energy Innovation Chair.

“They model and map out the grid in a village that wants to install either a solar system or a wind plant. They look for any stability issues that might arise out of this proposed project,” Pinard explains.

The wind feasibility data plus the assurance that the energy grid can handle the switch provides a clear plan of action—provided they get community buy-in.

“I think that’s the most important thing, building a good relationship with the community,” Pinard says. He has years of experience in creating community initiatives to introduce wind power to new places.

As far back as 20 years ago, Pinard volunteered with the Yukon Conservation Society (YCS) to create an energy committee, complete with an official energy coordinator. In 2014, Pinard and the YCS decided to introduce ETS in Whitehorse. They organized a conference, a workshop, and a pilot project that placed ETS units in over 45 homes to see how the system can work on a large scale. The next step of this project will be to combine ETS with the new wind turbines being built in Eagle Hill, and to hopefully expand the project to all homes in the Yukon.

"There's also a cultural aspect to this,” Pinard adds. Different communities have different needs. The Yukon, Nunavut, and the Northwest Territories are home to many Indigenous communities and projects must progress collaboratively from the beginning. To ensure clear communication, Pinard believes the best practice is to begin projects with energy working groups.

In the same way that having the YCS create and maintain their own energy committee allows them to take ownership of their own grid, working groups provide communities with a direct stake and say in the future of their energy system.

“An energy working group… is represented by different organizations in the community and helps the community itself to build their own knowledge capacity,” says Pinard. In this way, the entire community is involved in the decision making and has access to knowledge about how the system can be created and utilized.

From concept to creation

Pinard is so certain of the efficiency and potential of wind energy and ETS that he and his wife started a company, Wind Heat North Inc., to bring this combined technique as a method of winter heating to the Yukon, and the North as a whole.

He has the data to show that the wind is strong enough that these communities could be powering all their space heating through 100 per cent renewable wind energy.

“A lot of the initiatives that have started here, and a lot of the work that's happening here in Whitehorse and Yukon are being copied and applied in the other territories... I strongly believe that what we're doing here… will become standard technology all the way from Whitehorse to Iqaluit,” Pinard says.

Pinard is looking to a brighter, more sustainable future, where Whitehorse can be a center for renewable development in the North. For low-cost wind electricity, the wind turbine projects need to be scalable and the storage capacity has to be increased. But Pinard works at a steady pace and keeps his eye on the prize—a future powered by wind.

Engineers build more than just bridges. Building Tomorrows is a series that highlights the important contributions of engineers and the many ways they help to make our world a better place.